Interim report of the Committee on Mentally Abnormal Offenders.

- Great Britain. Committee on Mentally Abnormal Offenders

- Date:

- 1974

Licence: Open Government Licence

Credit: Interim report of the Committee on Mentally Abnormal Offenders. Source: Wellcome Collection.

5/12 (page 3)

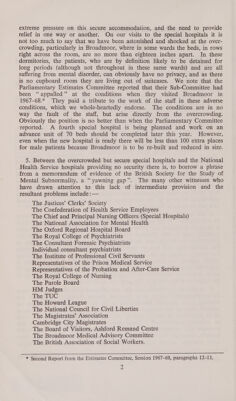

![years and are becoming more acute, particularly in relation to offenders. The Royal Commission on the Law Relating to Mental Illness and Mental Deficiency 1954-1957* said in paragraph 519 of their Report that dangerous patients should be specially accommodated in a few hospitals having suitable facilities for their treatment and custody, leaving other hospitals free to dispense with restrictive measures to the greatest possible extent; but such special accommodation has not been provided. Mean- while, the development of treatment in “open” conditions has made National Health Service hospitals increasingly reluctant to accept offenders: the number of hospital orders made by the courts has fallen year by year from a peak of 1,259 in 1966 to 924 in 1972. Custodial requirements cannot be reconciled with an “open door” therapeutic policyt, and when -offender patients abscond much time and trouble are involved in effecting their return. The nursing staff dislike the custodial role, and their numbers are insufficient to deal with dangerous patients. ‘They see it as the proper function of the prisons and special hospitals to cope with these people. There is also concern that offenders may harm or pilfer from non-offender patients. In the result, many psychiatric hospitals are unwilling to accept offender patients and do not make arrangements to provide for them. Even when offender patients have been accepted in National Health Service hospitals it may be found that they cannot be contained satisfactorily and have to be transferred to the already crowded special hospitals. The special hospitals can do very little to help themselves. They are bound to accept dangerous psychiatric cases from the open hospitals but have found it increasingly difficult to transfer patients to the psychiatric hospitals when they are no longer dangerous. ‘Two consequences follow from this: one is that many patients in the special hospitals need not be there for reasons of security ; and the special hospitals have to refuse admission to cases they could appropriately accept if they had room. 6. These problems rebound on the courts and the prisons and they are likely to increase as treatment of psychiatric cases is developed in district general hospitals. The courts are experiencing more and more difficulty in dealing with mentally abnormal offenders who need psychiatric treatment but who must be kept in secure conditions. Even where a hospital may be willing to accept such patients, judges are often reluctant to send offenders to “open door” hospitals because of the ease with which they can abscond and also because of the possibility that if they are found to be uncoopera- ‘tive and therefore untreatable they may soon be discharged into the com- munity. On the other hand these offenders may fail to satisfy the fairly stringent criteria for admission to a special hospital.t The result is that the courts may be obliged to impose a prison sentence as the only way out of the dilemma—an unsatisfactory outcome from almost every point of view. 7. Evidence received from the Home Office and from members of the Prison Medical Service has indicated growing concern among those respon- * Cmnd. 169, + The contradiction in aims has recently been the subject of a leading article in the British Medical Journal] (23 March 1974), t It.is noteworthy that of 12,000 offenders remanded for medical reports in 1971 only 173 were admitted to special hospitals from the courts. 3](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b32230540_0005.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)