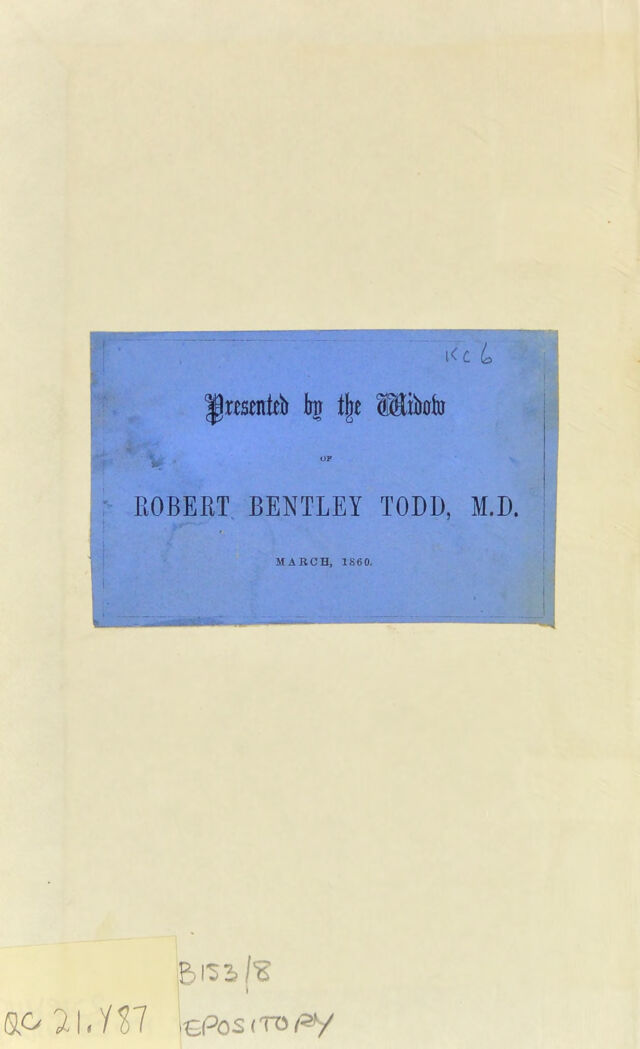

Volume 1

A course of lectures on natural philosophy and the mechanical arts / by Thomas Young.

- Thomas Young

- Date:

- 1845

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A course of lectures on natural philosophy and the mechanical arts / by Thomas Young. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by King’s College London. The original may be consulted at King’s College London.

101/670 page 67

![one sense indeed the remark is true ; thus one man can do no more hy a powerful machine in ten hours, than ten men can do hy a weaker machine in one hour ; but in other senses the assertion is often erroneous ; for by increasing the mechanical advantage to a given degi'ee we may in some cases considerably increase the performance of a machine without adding to the force. According to the nature of the force employed, and to the construction of the machine, a different calculation may be required for finding the best proportions of the forces to he employed ; but a few simple instances will serve to show the natui’e of the determination. Thus, in order that a smaller weight may raise a greater to a given vertical height, in the shortest time possible, by means of an inclined plane, the length of the plane must be to its height as twice the greater weight to the smaller,* so that the acting force may be twice as great as that which is simply required for the equilibrium. This may be shown experimentally, by causing three equal weights, supported on wheels, to ascend at the same time as.jnany inclined planes of the same height but of different lengths, by means of the descent of three other equal weights, connected with the former tlu'ee by threads passing over pullies. The length of one of the planes is twice its height, that of another considerably more, and that of a third less : if the weights begin to rise at the same time, the first wHl arrive at the top before either of the others. (Plate V. Fig. 76.) If a given weight, or any equivalent force, be employed to raise another equal weight by means of levers, wheels, pullies, or any similar powers, the greatest effect will be produced if the acting weight be capable of sus- taining in equilibrium a weight about twice and a half as great as itself. This proposition may be very satisfactorily illustrated by an experiment. Three double pullies being placed, independently of each other, on an axis, round which they move freely, the diameters of the two cylindrical por- tions which compose the first being in the ratio of 3 to 2, those of the ^ second as 5 to 2, and those of the third as 4 to 1, six equal weights are I attached to them in pairs, so that three may be raised by the descent of the I other three, on the princijile of the wheel and axis. If then we hold the • lower weights by means of threads or otherwise, and let them go, so that I they may begin to rise at the same instant, it will appear evidently that I the middle jmlley raises its weight the fastest; and consequently, that in this case, the ratio of 5 to 2 is more advantageous than either a much less or a much greater ratio. If the weight to be raised were very great in ])i’o- portion to the descending weight, the arrangement ought to be such that this weight might retain in equilibrium a weight about twice as great as that which is actually to be raised. If the descending weight were a hundred times as great as the ascending weight, the greatest velocity would be obtained in this case, by making the descending weight capable of holding in equilibrium a weight one ninth as great as itself. (Pbite VI. Fig. 77.) Ihe proportion required for the greatest effect is somewhat different when the heights through which both the weights are to move are limited, as they usually must be in practical cases. Here, if we suppose the opera- * Whewell’s Dyn. c. 4, §4.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21301840_0001_0101.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)