Volume 1

A course of lectures on natural philosophy and the mechanical arts / by Thomas Young.

- Thomas Young

- Date:

- 1845

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A course of lectures on natural philosophy and the mechanical arts / by Thomas Young. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by King’s College London. The original may be consulted at King’s College London.

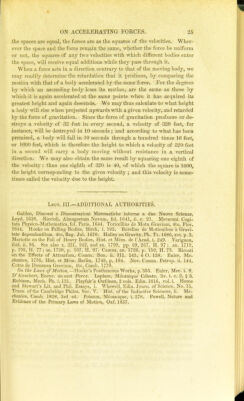

55/670 page 21

![LECTURE III. ON ACCELERATING FORCES. W E have liitherto only considered motion as already existing, without any regard to its origin or alteration ; we have seen that all undisturbed motions are equable and rectilinear; and that two motions represented by the sides of a parallelogram, cause a body to describe its diagonal by their joint effect. We are now to examine the causes which produce or destroy motion. Any cause of a change of the motion of a body with respect to a quiescent space, is called a force; that is, any cause which produces motion in a body at rest, or which increases, diminishes, or modifies it in a body which was before in motion. Thus the power of gravitation, which causes a stone to fall to the ground, is called a force; but when the stone, after descending down a hUl, rolls along a horizontal plane, it is no longer impelled by any force, and its relative motion continues unaltered, until it is gradually destroyed by the retarding force of friction. Its perseverance in the state of motion or rest in consequence of the inertia of matter, has sometimes been expressed by the term vis inertiae, or force of inertia; but it appears to be somewhat inaccurate to apply the term force to a property which is never the cause of a change of motion in the body to which it belongs. It is a necessary condition, in the definition of force, that it be the cause of a change of motion with respect to a quiescent space. For if the change were only in the relative motion of two points, it might happen without the operation of any force: thus, if a body be moving Avithout disturbance, its motion with respect to another body, not in the line of its direction, will be peiqietually changed: and this change, considered alone, would [appear to] indicate the existence of a repulsive force; and, on the other hand, two bodies may be subjected to the action of an attractive force, while their distance remains nnaltered, in consequence of the centrifugal effect of a rotatory motion. (Plate I. Fig. 9.) Tlie exertion of an animal, the unbending of a bow, and the communi- cation of motion by impulse, are familiar instances of the actions of forces. We must not imagine that the idea of force is naturally connected with that of labour or difficulty; this association is only derived from habit, since our voluntary actions are in general attended with a certain effort, which leaves an impression ahnost inseparable from that of the force that it calls into action. It is natural to inquire in what immediate manner any force acts, so as to produce motion ; for instance, by what means the earth causes a stone to gravitate towards it. In some cases, indeed, we are disposed to imagine that we understand better [tolerably well] the nature of the action of a force, as, when a body in motion strikes another, we conceive, that the impenetrability of matter is a sufficient cause for the communication of motion, since the first body cannot continue its course without displacing](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21301840_0001_0055.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)