Volume 1

A course of lectures on natural philosophy and the mechanical arts / by Thomas Young.

- Thomas Young

- Date:

- 1845

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A course of lectures on natural philosophy and the mechanical arts / by Thomas Young. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by King’s College London. The original may be consulted at King’s College London.

74/670 page 40

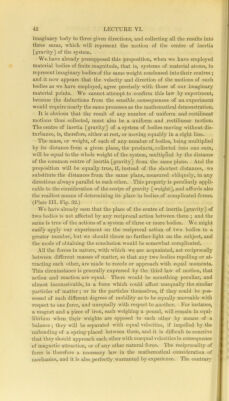

![its distance are equal: thus two multiplied by one is equal to one multi- plied by two. (Plate II. Fig. 29.) This point is most commonly called the centre of gravity; it has also sometimes been denominated the centre of position. Since it has many proi:>erties independent of the consideration of gi’avity, it ought not to derive its name from gravitation, [but as custom has famiharized the term, we deem it better to retain it.] The centre of inertia [gravity] of any two bodies initially at rest, remains at rest, notwithstanding any reciprocal action of the bodies ; that is, not- withstanding any action which affects the single particles of both equally, in increasing or diminishing their distance. For it may be shown, from the principles of the composition of motion, that any force, acting in tliis manner, will cause each of the two bodies to describe a space proportional to the magnitude of the other body : thus a body of one pound will move through a space twice as gi-eat as a body of two pounds weight, and the remaining parts of the original distance will stUl be divided in the same proportion by the original centre of inertia [gravity], which therefore stUl remains the centre of ineidia [gravity], and is at rest. And it follows also, that if the centre of inertia [gravity] is at first in motion, its motion wUl not be affected by any reciprocal action of the bodies. This important property is very capable of experimental illustration; first observing, that all known forces are reciprocal, and among the rest the action of a spring; we place two unequal bodies so as to be separated when a spring is set at liberty, and we find that they describe, in any given interval of time, distances which are inversely as their weights ; and that consequently the place of the centre of inertia [gravity] remains un- altered. They may either be made to float on water, or may be suspended by long threads; the spring may be detached by burning a thread that confines it, and it may be observed whether or no they strike at the same instant two obstacles, placed at such distances as the theory requires ; or if they are suspended as pendulums, the arcs which they describe may be measured, the velocities being always nearly proportional to tliese arcs, and accurately so to their chords. (Plate II. Fig. 30.) The same might also be shown of attractive as well as of repulsive forces. For instance, if we placed ourselves in a small boat, and pulled a rope tied to a much larger one, we should draw ourselves towards the large boat with a motion as much more rapid than that of the large boat, as its weight is greater than that of our own boat; and the two boats would meet in their common centre of inertia [gravity], supposing the resistance of the water inconsiderable. Having established this property of the centre of inertia [gravity] as a law of motion, we may derive from it the true estimate of the quantity of motion in different bodies, in a much more satisfactory manner than it has usually been explained. For since the same reciprocal action produces, in a body weighing two pounds, only half the velocity that it ju’oduces in a body weighing one pound, the cause being the same, the effects must be considered as equal, and the quantity of motion must always be measured by the joint I’atio of mass to mass, and velocity to velocity ; that is, by the](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21301840_0001_0074.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)