Volume 1

A course of lectures on natural philosophy and the mechanical arts / by Thomas Young.

- Thomas Young

- Date:

- 1845

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A course of lectures on natural philosophy and the mechanical arts / by Thomas Young. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by King’s College London. The original may be consulted at King’s College London.

75/670 page 41

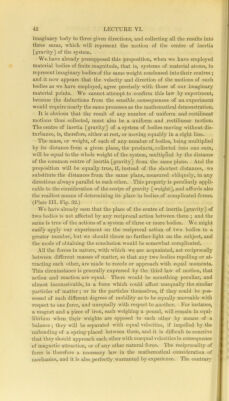

![ratio of the products, obtained by multiplying the weight of each body by the number expressing its velocity; and these products are called the momenta of the bodies. We appear to have deduced this measure of motion from the most unexceptionable arguments, and we shall have occa- sion to apply the momentum thus estimated as a true measure of force ; at the same time that we allow the practical importance of considering, in many cases, the efficacy of forces, according to another criterion, when we multiply the mass by the square of the velocity, in order to determine the energy; yet the true quantity of motion, or momentum, of any body, is always to be understood as the product of its mass into its velocity. Thus a body weighing one pound, moving with the velocity of a hundred feet in a second, has the same momentum and the same quantity of motion as a body of ten pounds, moving at the rate of ten feet in a second. We may also demonstrate experimentally, by means of Mr. Atwood’s machine [Plate I. Fig. 11], that the same momentum is generated, in a given time, by the same preponderating force, whatever may be the quan- tity of matter moved. Thus, if the preponderating weight be one sixteenth of the whole weight of the boxes, it will fall one foot in a second instead of 16, and a velocity of two feet will be acquired by the whole mass, instead of a velocity of 32 feet, which the preponderating weight alone would have acquired. And when we compare the centrifugal forces of bodies revolving in the same time at different distances from the centre of motion, we find that a greater quantity of matter compensates for a smaller force ; so that two balls connected by a wire, with liberty to slide either way, will retain each other in their respective situations when their common centre of inertia [gravity] coincides with the centre of motion ; the centrifugal force of each particle of the one being as much greater than that of an equal particle of the other, as its weight or the number of the particles is smaller. But it is not enough to determine the centre of inertia [gravity] of two bodies only, considered as single points; since in general a much greater number of points is concerned ; we must therefore define the sense in which the term is in this^case to be a2)plied. We proceed by considering tlie first and second of three or more bodies, as a single body equal to both of them, and placed in their common centre of inertia [gravity] ; determining the centre of inertia [gravity] of this imaginary body and the third body, and continuing a similar process for all the bodies of the system. And it matters not with whicli of the bodies we begin the ojjeration, for it may be demonstrated that the point thus found will be the same l)y whatever steps it be determined. When we come to consider the properties of the same point as the centre of gravity [weight] we shall be able to produce an ex- perimental proof of this assertion, since it will be found that there is only one point in any system of bodies which possesses these properties. (Plate III. Fig. 31.) We may always represent the motion of the centre of inertia [gravity] of a system of moving bodies, l)y supposing their masses to be united into one body, and tins body to receive at once a momentum equal to that of each body of the system, in a direction parallel to its motion. 'I’liis may often be the most conveniently done Iiy referring all the motions of this](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21301840_0001_0075.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)