Volume 1

A course of lectures on natural philosophy and the mechanical arts / by Thomas Young.

- Thomas Young

- Date:

- 1845

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A course of lectures on natural philosophy and the mechanical arts / by Thomas Young. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by King’s College London. The original may be consulted at King’s College London.

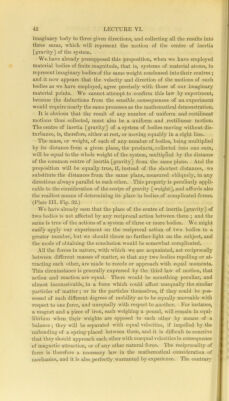

78/670 page 44

![the same kind. For the apparent difference in the velocity with which different substances fall through the atmosphere, is only owing to the resistance of the air, as is sometimes shown by an experiment on a feather and a piece of gold falling in the vacuum of an air pump ; hut the true cause was known long before the invention of this machine, and it is dis- tinctly explained in the second book of Lucretius : “ In water or in air when weights descend, The heavier weights more swiftly downwards tend. The limpid waves, the gales that gently play. Yield to the weightier mass a readier way. But if the weights in empty space should fall. One common swiftness we should find in all.” We are therefore to suppose, that the different weights of equal hulks of different substances depend merely on the greater or less number of parti- cles contained in a given space, independently of any other characters that may constitute the specific differences of those substances. In some cases it is necessary to consider the sum of the masses of two bodies, in order to estimate their mutual action ; that is, when we wish to know the whole relative motion of two bodies with respect to each other ; for here we must add together their single motions with respect to the centre of inertia [gravity], which are inversely in the same ratio. This consideration is sometimes of use in determining the action of the sun on the several planets. If two bodies act on each other with forces proportional to any power of their distance, for instance to the square or the cube of the distance, the forces wiU also he proportional to the same power of either of their dis- tances from their common centre of inertia [gravity]. Thus, in the planetary motions, when one body performs a revolution by means of the attractive force of another, this other cannot remain absolutely at rest; hut because it is more convenient to determine the effect of the attraction as' directed to a fixed point, we consider the force as residing in the common centre of inertia [gravity] of the two bodies, which remains at rest, as far as the mutual actions of those bodies only are concerned, and it may he shown, that the force diminishes as the square of the distance of the bodies, either from this point or from each other, increases. The reciprocal forces of two bodies may therefore he considered as tending to or from their common centre of inertia [gravity] as a fixed point; hut it often happens that the difference of magnitude being very great, the motion of one of the bodies may be disregarded. Tims we usually neglect the motion of the sun, in treating of the planetary motions produced by his attraction, although, by means of very nice observations, this motion becomes sensible. But it is utterly beyond the power of our senses to discover the reciprocal motion of tlie earth produced by any teri’estrial cause, even by the most copious erup- tion of a volcano, although, speaking mathematicallj’', we cannot deny that whenever a cannon ball is fired upwards, the whole globe must suffer a minute depression in its course. The boast of Archimedes was therefore accomj)anied by an unnecessary condition : “ give me,” said he, “ but a firm support, and 1 will move the earthbut, granting him his support.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21301840_0001_0078.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)