Glass and British pharmacy, 1600-1900 : a survey and guide to the Wellcome Collection of British glass / J.K. Crellin and J.R. Scott.

- Wellcome Institute of the History of Medicine

- Date:

- 1972

Licence: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Credit: Glass and British pharmacy, 1600-1900 : a survey and guide to the Wellcome Collection of British glass / J.K. Crellin and J.R. Scott. Source: Wellcome Collection.

19/96 (page 3)

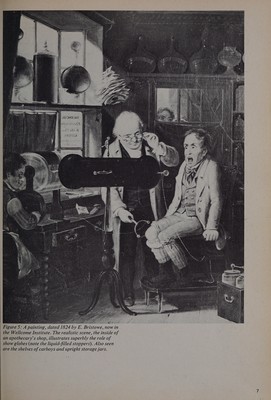

![through the wholesaling of drugs. They frequently developed from grocers who found it profitable to specialize in the increasingly wide range of drugs available, many being imported’. According to Harvey in 1676 some were also selling chemical preparations at the time, for ‘they buy great quan- tities of them from the chymists at much cheaper rates, then they will sell lesser proportions to particular persons’ ?°. Just when the druggists became generally in- volved in small-scale manufacturing and retailing drugs is difficult to say, but it was almost certainly a slow development that had become well estab- lished by the middle of the 18th century?*. That druggists should have commenced retailing drugs is not surprising, for domestic medicine was prac- tised widely, and, with an increasing population, it must have been easy to encroach on the retailing activities of apothecaries who were giving more and more attention to medical practice. Also uncertain is just when the druggists began to dispense prescriptions regularly, for it must be remembered that throughout the period being considered the apothecary/general practitioner commonly did his own dispensing (or left it to his apprentice!), the chemist and druggist gradually taking over the filling of physicians’ prescriptions. This situation was generally well established by the early decades of the 19th century ?°, though _ when the apothecaries grumbled about chemists and druggists dispensing widely for physicians in the 1790s, they may have been overstating the situation as the number of physicians was still comparatively small ??. _ A further uncertainty in the evolution of the chemist and druggist concerns the association of the two occupations (that of the ‘chemist’ with that of the ‘druggist’). This, too, must have been something of an ad hoc process, though a natural | one. The 18th-century ‘chemist’ was generally as much concerned with producing traditional ‘galenic’ preparations as with chemical substances even though in the post-Paracelsian era ‘chemical pharmacy’ had been divided sharply from ‘galeni- cal pharmacy’. For economic reasons the chemist had fairly wide activities, often including the sale of proprietary and other medicines ??. Even so it was only in the last decades of the century that the composite term ‘chemist and druggist’ came into common use, at least in London, while those with specialist concern in chemistry (as distinct from pharmacy) came to be known as ‘operative chemists’ 23. During the 19th century, especially following the formation of the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain in 1841, chemists and druggists pharmacists of the nation, although, as mention- ed, large numbers of apothecary/general practi- tioners continued to dispense their own prescrip- tions. It has to be remembered, too, that some | chemists and druggists did a great deal of counter prescribing, so that the Hungarian physician J. E. Feldmann seemed confused over the distinctions between chemists and druggists and apothecaries in his diatribe (published in 1843) against English medical organisations: When passing along the street, it is a physical impossibility to look into any apothecary’s shop, except through the open door, the window is so blocked up with the most multifarious objects. From the middle of the panes glare huge, coloured glasses, yellow, red, and blue, having inscribed upon them certain talismanic characters... the lower part of the window is occupied, or rather dressed out, as the term is, with numerous small bottles for aromatic liquids, &c., larger ones with lavender water, bottles of eau de Cologne: horse-hair gloves: syringes of every size and material: an infinite variety of soaps, and, lastly, innumerable boxes of pills... His Shop is, in fact, a real museum, where may be found everything, excepting what ought to be met with in a regular establishment of this description. Notwithstanding the highly decorated words over his door, of — CHEMIST AND DRUGGIST, he can scarcely be called the latter, who is, properly a drug merchant... There is also to be seen in almost every apothe- cary’s shop, a door upon which are displayed, oftentimes in several languages, the words ‘Consultation room’ where he receives his patients, either for giving advice, breathing a vein, extracting a tooth, &c??. Needless to say, in the light of the complex medico-pharmaceutical scene, there was much inter-professional rivalry between apothecaries and chemists and druggists, and it is pertinent to ask if their establishments reflected this rivalry, apart from commercial competition such as pro-. moting the sale of side lines (see p10). Certainly, as will be mentioned later, many decorative containers came into prominence with the rapid 19th-century inerease in numbers of chemists and druggists, and it is significant that Culverwell, around 1850, compared favourably the chemist and druggist’s shop with that of an apothecary: A druggist’s shop with open door and a licensed tenant within, and a cheerful countenance is a standing advertisement and must necessarily facilitate consultation which [is precluded by] the closed doors, a sombre lamp, and the pageantry of being ushered in and out [of an](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b33294185_0019.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)