Glass and British pharmacy, 1600-1900 : a survey and guide to the Wellcome Collection of British glass / J.K. Crellin and J.R. Scott.

- Wellcome Institute of the History of Medicine

- Date:

- 1972

Licence: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Credit: Glass and British pharmacy, 1600-1900 : a survey and guide to the Wellcome Collection of British glass / J.K. Crellin and J.R. Scott. Source: Wellcome Collection.

22/96 (page 6)

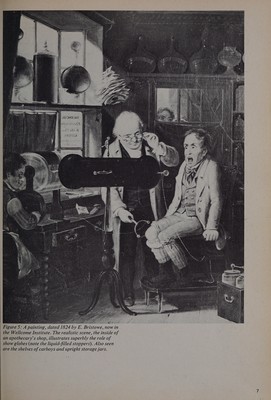

![iantly lit by oil lamps and lined with shops open till ten o’clock in the evening: The spirit booths are particularly tempting, for the English are in any case fond of strong drink. Here crystal flasks of every shape and form are exhibited; each one has a light behind which makes all the different coloured spirits sparkle®®. Gottling also mentions lights — he refers to Argand’s burners — placed behind the liquid- filled display vessels which acted as a lens (the ‘watery lights’ of Walter de la Mare), and it seems that this practice was widespread until this cen- tury. In 1900 the Chemist and Druggist described a chemist’s shop in Dover that had recently bten refitted, and had behind every carboy a Welsbach gaslight*°. Innumerable formulae for the coloured liquids were published, the earliest one found being in Gray’s Supplement to the Pharmacopoeia of 1824 7% But apart from filling water-white, cylindrical, specie jars with coloured waters (or even painting them on the outside, sometimes with symbols, or putting tin crowns around the neck (see Figs /3, 18 and 19)), many cylindrical jars placed in the window may well have been general purpose type used for storage, as suggested by the eighty or so containers in the windows of Price & Co (Fig /). In other words, windows, before their display value became fully realised, were sometimes an extension of shop-shelving. Such general storage containers were bottle green, or, more rarely, of an amethyst or blue colour, 12 to 16 inches high, and of capacity around one gallon. Though the quality of the bottles, of which large numbers sur- vive, is generally poor (but cf Fig 23), they were often made pleasing to the eye by elegant labelling and the addition of japanned lids. The use of these upright storage jars, combining utility and decoration, persisted throughout the 19th century, until they were gradually replaced by the “Winchester quart’ (see p13). b. Carboys and show globes The same dual purpose of utility and decoration is relevant to the majority of globe-shaped car- boys. Most that survive are one gallon in capacity, and of bottle green glass, the type that Jacob Bell broke during his apprenticeship in the 1820s. He illustrated this misdemeanour in his note book ‘A List of Fractures’, labelling the drawing ‘a green show bottle 13 -- 6!’4?. Apart from elegant label- ling, an overall, hand-painted decoration was sometimes applied to the green carboys (cf Fig 36), so that they matched the attractiveness of the rarer amethyst or blue glass carboys. that survive being of water-white glass (Fig 4/), while the comparatively few green ones are generally of a light green glass, rather than the usual dark bottle green. Generally, they have matching stoppers (in contrast with the majority of globe-shaped carboys). When the pear-shape was introduced is uncertain, though none we have studied appears to be earlier than 1800, post- dating many of globe-shape. This suggests that the latter became generally used during the eighteenth century, while the pear-shaped style only became widespread in the 19th century, probably among the growing numbers of chemists and druggists (see below). The earliest illustration of the pear- shape that has been found is in Jacobson and Sons’ catalogue of 1837 +43. Yet another version of the carboy was one specially designed for window decoration. This has already been referred to as the ‘large show globe’ listed in the New York Daily Advertiser advertisement of 178944. Probably all of this type globular stopper (cf Fig 5), a style undoubtedly common by the 1820s (Figs 4 and 5) serving asa forerunner for the much larger show globes to be mentioned later (p8). Some of them had stoppers filled with different coloured liquids as mentioned by GOottling in the 1780s (see above). Dickens also noted the coloured stoppers many years later: when Tom Pinch, assistant to Seth Pecksniff, went into Salisbury to meet a new apprentice he filed in time by looking at the shops which included ‘chemists’ shops, with their great glowing bottles (with smaller repositories of brightness in their very stoppers); and in their agreeable compro- mises between medicine and perfumery, in the shape of toothsome lozenges and virgin honey’ *°. It is clear from illustrations (eg that of Price and Co) that the less elaborate globe- and pear-shaped carboys, already mentioned, decorated windows (as did the upright storage jars) along with the special, elegant versions. John Chaloner provided some confirmation by his reminiscence, published in 1889, on Fires by Focussing the Sun’s Rays. He remarked on ‘old-fashioned spherical gallon bottles, one of which, filled with dilute sulphuric acid, [was] placed on a shelf exposed to direct sun’s rays, actually [igniting] a piece of brown paper which was there by accident. It burst into a blaze. The shelf had several charred depressions in the wood from the same cause’ *®. The use of carboys in windows is a'reminder of Charles La Wall’s hypothesis about the origin of coloured show globes. He believed that they evolved from vessels used for preparing tinctures by maceration, the crude drug and the menstruum](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b33294185_0022.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)