Molyneux's question : vision, touch, and the philosophy of perception / Michael J. Morgan.

- Morgan, Michael J.

- Date:

- 1977

Licence: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Credit: Molyneux's question : vision, touch, and the philosophy of perception / Michael J. Morgan. Source: Wellcome Collection.

30/236 (page 18)

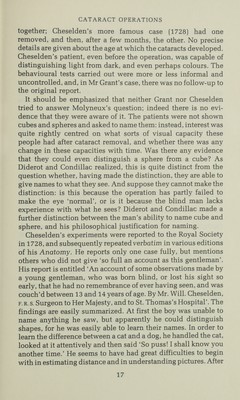

![MOLYNEUX'S QUESTION often forgot which was the cat, and which the dog, he was asham'd to ask; but catching the cat (which he knew by feeling] he was observ'd to look at her stedfastly, and then letting her down again, said. So Puss! I shall know you another time. He was very much surpriz'd, that those things which he had lik'd best, did not appear most agreeable to his eyes, expecting those persons would appear most beautiful that he lov'd most, and such things to be most agreeable to his sight that were so to his taste. We thought he soon knew what pictures represented, which were shew'd to him, but we found afterwards we were mistaken; for about two months after he was couch'd, he discovered at once, they represented solid bodies; when to that time he consider'd them only as party-colour'd planes, or surfaces diversified with variety of paint; but even then he was no less surpriz'd, expecting the pictures would feel like the things they represented, and was amaz'd when he found those parts, which by their light and shadow appear'd now round and uneven, felt only flat like the rest; and asked which was the lying sense, feeling, or seeing? Being shewn his father's picture in a locket at his mother's watch, and told what it was, he acknowledged a likeness, but was vastly surpriz'd; asking, how it could be, that a large face could be express'd in so little room, saying, it should have seem'd as impossible to him, as to put a bushel of any thing into a pint. At first, he could bear but very little sight, and the things he saw, he thought extreamly large; but upon feeling things larger, those first seen he conceiv'd less, never being able to imagine any lines beyond the bounds he saw; the room he was in he said, he knew to be but part of the house, yet he could not conceive that the whole house could look bigger. Before he was couch'd, he expected little advantage from seeing, worth undergoing an operation for, except reading and writing; for he said, he thought he could have no more pleasure in walking abroad than he had in the garden, which he could do safely and readily. And even blindness he observ'd, had this advantage, that he could go any where in the dark much better than those who can see; and after he had seen, he did not soon lose this quality, nor desire a light to go around the house in the night. He said, every new object was a new delight, and the pleasure was so great, that he wanted ways to express it; but his gratitude to his operator he could not conceal, never seeing him for some time without tears of joy in his eyes, and other marks of affection: and if he did not happen to come at any time when he was expected, he would be so griev'd, that he could not forbear crying at his disappointment. A year after first seeing, being carried upon Epsom Downs, and observing a large prospect, he was exceedingly delighted with it, and call'd it a new kind of seeing. And now being lately couch'd of his other eye, he says, that objects at first appear'd large to this eye, but not so large as they did at first to the other; and looking upon the 20](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/B18024257_0031.JP2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)