Traffic in towns : a study of the long term problems of traffic urban areas. Reports of the steering group and working group appointed by the Minister of Transport.

- Great Britain. Ministry of Transport

- Date:

- 1963

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Traffic in towns : a study of the long term problems of traffic urban areas. Reports of the steering group and working group appointed by the Minister of Transport. Source: Wellcome Collection.

36/248 (page 16)

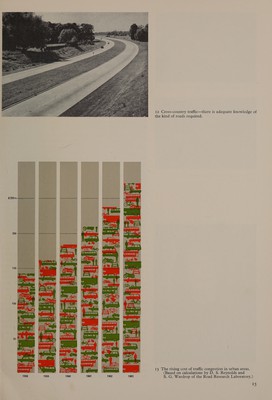

![1§ The conflict—cyclists and vehicles (High Street, Oxford). 16 The ‘Black Widow’ poster of 1946, with a message so stark that it seemed to give offence, and thus lost its point. 16 Allowing for the increase of traffic since then, and for the fact that the cost of congestion increases faster than the growth of traffic, the comparable figure for 1963 would be over £250 millions (Figure 13). It is a difficult matter to quantify because the journeys involved are of such complexity— there are people held up in buses, for example, some of whom may be going about important business where time really is ‘money’, but others may be merely out for a day’s window shopping. There are delays to commercial vehicles of many kinds. There are delays to commuters in their own cars, where the only real hardship may be the deprivation of an extra half hour in bed in the morning. On the other hand there are business people to whom the use of a car is a very great convenience and where delays are expensive as well as irksome. To delays so various as these it is indeed difficult to assign any meaningful cost, but it must nevertheless be generally true that an enormous amount of time and money is wasted in urban traffic delays throughout the country. 14. It should be emphasised that what is primarily involved in traffic delays is a most serious interference with the swift movement of vehicles, and hence with the economic efficiency of the country. Accidents 15. The multiplication and increasing usage of vehicles has, unhappily, led to a great many accidents. The cause of accidents has been the subject of much dispute, and some of the reasons advanced bear the imprint of sectional interests. In theory it would seem beyond dispute that if all road users would take conditions as they find them, and exercise unremitting care al] the time, there would be no accidents other than those caused by an act of God or some unpredictable mechanical failure. Human beings being what they are, however, errors and miscalculations ~ creep in, and though these are small in comparison with the total amount . of movement that takes place they are nevertheless sufficient to add up to a formidable total. 16. The number of accidents is not directly proportional to the total number of vehicles in circulation, for it is a fact that in 1934 (the peak year for accidents before the War) there were 238,946 casualties with only 2,405,392 vehicles in use, whereas in 1960 the corresponding figure was 347,551 casualties with some 9,383,140 vehicles. Thus a fourfold increase in the number of vehicles has led only to a 45% imcrease in casualties. There are many reasons to account for this, including improved techniques for the control of intersections, elimination of “blackspots,’ better vehicle design, and the gradual improvement of standards of road usage. Nevertheless there is a depressing consistency about the figures— month by month, holiday period by holiday period, year by year—which seems to indicate that from a given number of potentially conflicting traffic movements a predictable number of accidents will take place. The lesson seems to be—assuming no readiness by the public to revolutionise its highway behaviour—that a radical improvement of the situation will come only from sweeping physical changes designed to reduce the sheer number of opportunities for conflict. 17. It is understandable that accidents should be particularly numerous in the crowded conditions of towns, and 73° of all casualties take place in urban areas (as defined by the existence of a 30 m.p.h. speed limit) (Figure 19). Motor vehicles of one kind or another are of course involved in most of these accidents. There is, however, a difference of incidence inasmuch as the proportion of fatal accidents is greater in open areas than in built-up areas—presumably due to the higher speed at which accidents take place. Figure 10 shows the extent of the unhappy conflict, particularly in urban areas, between vehicles on the one hand and pedes- trians and cyclists on the other. 18. It is sometimes represented that traffic accidents as a social evil do not bear comparison with deaths and injuries due to fire, accidents in the home and industry, or even to natural causes such as cancer. In](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b32171092_0036.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)