The constitution of man : considered in relation to external objects / by George Combe.

- George Combe

- Date:

- 1844

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The constitution of man : considered in relation to external objects / by George Combe. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library at Yale University, through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library at Yale University.

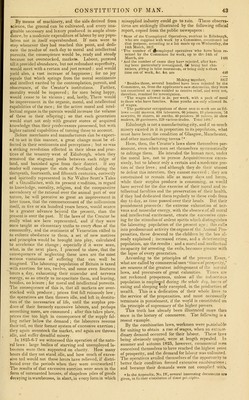

51/460 page 43

![By means of machinery, and the aids derived from science, the ground can be cultivated, and every ima- ginable necessary and luxury produced in ample abun- dance, by a moderate expenditure of labour by any popu- lation not in itself superabundant. If men were to stop whenever they had reached this point, and dedi- cate the residue of each day to moral and intellectual pursuits, the consequence would be, ready and steady because not overstocked, markets. Labour, pursued till it provided abundance, but not redundant superfluity, would meet with a certain and just reward : and would yield also, a vast increase of happiness ; for no joy equals that which springs from the moral sentiments and intellect excited by the contemplation, pursuit, and observance, of the Creator's institutions. Farther, morality would be improved ; for men being happy, would cease to be vicious ; and, lastly, There would be improvement in the organic, moral, and intellectual capabilities of the race ; for the active moral and intel- lectual organs in the parents would increase the volume of these in their offspring; so that each generation would start not only with greater stores of acquired knowledge than their predecessors possessed, but with higher natural capabilities of turning these to account. Before merchants and manufacturers can be expect- ed to act in this manner, a great change must be ef- fected in their sentiments and perceptions ; but so was a striking revolution effected in their ideas and prac- tices of the tenantry west of Edinburgh, when they removed the stagnant pools between each ridge of land, and banished ague from their district. If any reader will compare the state of Scotland during the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries, correctly and spiritedly represented in Sir Walter Scott's Tales of a Grandfather, with its present condition, in regard to knowledge, morality, religion, and the comparative ascendency of the rational over the animal part of our nature, he will perceive so great an improvement in later times, that the commencement of the millennium itself, in five or six hundred vears hence, would scarce be a greater advance beyond the present, than the present is over the past. If the laws of the Creator be really what are here represented, and if they were once taught as elementary truths to every class of the community, and the sentiment of Veneration called in to enforce obedience to them, a set of new motives and principles would be brought into play, calculated to accelerate the change ; especially if it were seen, what, in the next place, I proceed to show, that the consequences of neglecting these iaws are the most serious visitations of suffering that can well be imagined. The labouring population of Britain is taxed with exertion for ten, twelve, and some even fourteen hours a day, exhausting their muscular and nervous energy, so as utterly to incapacitate them, and leaving, besides, no leisure ; for moral and intellectual pursuits. The consequence of this is, that all markets are over- stocked with produce ; prices first fall ruinously low; the operatives are then thrown idle, and left in destitu- tion of the necessaries of life, until the surplus pro- duce of their formerly excessive labours, and perhaps something more, are consumed ; after this takes place, prices rise too high in consequence of the supply fal- ling rather below the demand ; the labourers resume their toil, on their former system of excessive exertion ; they again overstock the market, and again are thrown idle, and suffer dreadful misery. In 1825-6-7 we witnessed this operation of the natu- ral laws : large bodies of starving and unemployed la- bourers were then supported on charity. How many hours did they not stand idle, and how much of exces- sive toil would not these hours have relieved, if distri- buted over the periods when they were overworked 1 The results of that excessive exertion were seen in the form of untenanted houses, of shapeless piles of goods decaying in warehouses, in short, in every form in which misapplied industry could go to ruin. -These observa- tions are strikingly illustrated by the following official report, copied from the public newspapers : ' State of the Unemployed Operatives, resident in Edinburgh, who are supplied with work by a Committee, constituted tor that purpose, according to a list made up on Wednesday, the 14th March, 1827. 'The number of ^employed operatives who ha-ve been re- mitted by the Committee for work, up to the 14th of March, are ] 131 ' And the number of cases they hav<> rejected, after hav- ing been particularly investigated, far being bad cha- racters, giving in false statements, or being only a short time out of work, &c. &c. are 446 Making together, 1927 ' Besides those, several hundred have been rejected by the Committee, as, from the applicants's own statements, they were not considered as cases entitled to receive relief, and were not, therefore, remitted for investigation. ' The wages allowed is 5s. per week, with a peck of meal to those who have families. Some youths are only allowed 3s. of wages. ' The particular occupations of those sent to work are as fol- lows :—242 masons. 634 labourers, 66 joiners, IS plasterers, *<6 sawyers. 19 slaters, 45 smiths, 40 painters. 36 tailors, 55 shoe makers, 20 gardeners. 229 various trades. Total 14S1.' Edinburgh is not a manufacturing city, and if so much misery existed in it in proportion to its population, what must have been the condition of Glasgow, Manchester, and other manufacturing towns 1* Here, then, the Creator's laws show themselves par- amount, even when men set themselves systematically to infringe them. He intended the human race, under the moral law, not to pursue Acquisitiveness exces- sively, but to labour only a certain and a moderate por- tion of their lives ; and although they do their utmost to defeat this intention, they cannot succeed ; they are constrained to remain idle as many days and hours, while their surplus produce is consuming, as would have served for the due exercise of their moral and in- tellectual faculties and the preservation of their health, if they had dedicated them regularly to these ends from day to day, as time passed over their heads. But their punishment proceeds : the extreme exhaustion of ner- vous and muscular energy, with the absence of all moral and intellectual excitement, create the excessive crav- ing for the stimulus of ardent spirits which distinguishes the labouring population of the present age ; this calls into predominant activity the organs of the Animal Pro- pensities, these descend to the children by the law al- ready explained ; increased crime, and a deteriorating population, are the results : and a mora! and intellectual incapacity for arresting the evils, becomes greater with the lapse of every generation. According to the principles of the present Essay, - what are called by commercial men ' times of prosperity,' are seasons of the greatest infringement of the natural laws, and precursors of great calamities. Times are not reckoned prosperous, unless all the industrious population is employed during the whole dry, hours of eating and sleeping only excepted, in the production of wealth. This is a dedication of their whole lives to the service of the propensities, and must necessarily terminate in punishment, if the world is constituted on the principle of supremacy of the higher powers. This truth has already been illustrated more than once in the history of commerce. The following is a resent example. By the combination laws, workmen were punishable for unitino- to obtain a rise of wages, when an extraor- dinary demand occurred for their labour. These laws beino- obviously unjust, were at length repealed. In summer and autumn 1825, however, commercial men conceived themselves to have reached the highest point of prosperity, and the demand for labour was unlimited. The operatives availed themselves of the opportunity to better their condition formed extensive combinations ; and because their demands were not complied with, *In the Appendix, No. IV, several interesting documeats ara eiven, in further elucidation of these principle.*.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21029131_0051.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)