Memoirs of the early Italian painters / by Anna Jameson; thoroughly revised and in part rewritten by Estelle M. Hurll.

- Anna Brownell Jameson

- Date:

- 1899

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Memoirs of the early Italian painters / by Anna Jameson; thoroughly revised and in part rewritten by Estelle M. Hurll. Source: Wellcome Collection.

268/335 page 226

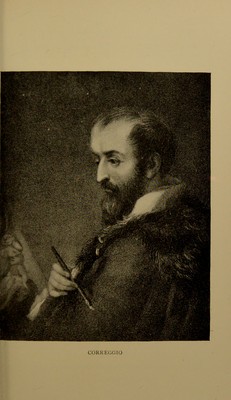

![have been engraved, but there is no proof of the authenticity of any. One of the most interesting is in the Parma Gallery, said to be by his own hand, but not accredited by critics.] The father of Correggio, Pellegrino Allegri, who survived him, repaid the twenty-live gold crowns which his son had received in advance for work he did not live to complete. The only son of Correggio, Pomponio Quirino Allegri, became a painter, but never attained to any great reputation, and ap- pears to have been of a careless, restless disposition. I will now give some account of Correggio’s works. His two greatest performances — the dome of the San Giovanni and that of the cathedral of Parma — have been mentioned. His smaller pictures, though not numerous, are dispersed through so many galleries that they cannot be said to be rare. It is remarkable that they are very seldom met with in the possession of individuals, but, with few exceptions, are to be found in royal and public collections. In our National Gallery are five pictures by Correggio: two are studies of angels’ heads,1 which, as they are not found in any of the existing frescoes, are supposed to have formed part of the composition in the San Giovanni, which, as already related, was destroyed. The other three are among his most celebrated works. The first, Mercury teaching Cupid to read in the presence of Venus, is an epitome of all the qualities which characterize the oil-painter; that peculiar smiling grace which is the expression of a kind of Elysian happiness, and that flowing outline, that melting softness of tone, which are quite illusive. “ Those who may not perfectly understand what artists and critics mean when they dwell with rapture on Correggio’s wonderful chiaroscuro should look well into this picture. They will perceive that in the painting of the limbs they can look through the shadows into the substance, as it might be into the flesh and blood; the shadows seem mutable, accidental, and aerial, as if between the eye and the colors, and not incorporated with them. In this lies the inimitable excel- lence of Correggio.” 2 This picture was painted for Eederigo Gonzaga, duke of Mantua; it was brought to England in 1629, when the Man- 1 [These are marked in the catalogue as being “ after Correggio.”] 2 [Mrs. Jameson’s] Public Galleries of Art [in or near London, vol. i. p. 33], in which there is a history of the picture, too long to be inserted here.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b24877888_0268.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)