Teetotalism in relation to chemistry and physiology : the substance of a lecture delivered in the Music Hall, Leeds, April 9th, 1851, under the auspices of the Temperance Society / by Dr. Frederick R. Lees.

- Frederic Richard Lees

- Date:

- [between 1800 and 1899?]

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Teetotalism in relation to chemistry and physiology : the substance of a lecture delivered in the Music Hall, Leeds, April 9th, 1851, under the auspices of the Temperance Society / by Dr. Frederick R. Lees. Source: Wellcome Collection.

7/12 (page 7)

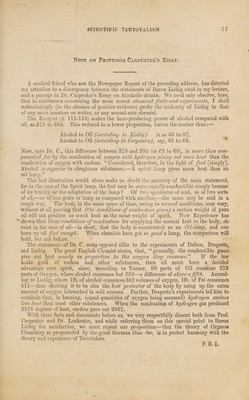

![Ry harm enough there, it does pass on iuto the system, and may subsequently he found in the blood and the secretions and excretions—save the portion that becomes decomposed by its union with oxygen in the blood. Indeed, it is the matter of the nervous centres for which alcohol has the most apparent affinity—not that of the stomach—and there is no reason whatever for asserting that it disunites itself with the water of the vital tissues. It will unite with all the water it meets with, equally, and this tendency to unite with the essential water of the vital-tissues (or, in other words, to absorb it) creates the local reaction called inflammation and redness. Notwithstanding distilled alcohol is admitted to be so bad, the undistilled is somehow a very‘good creature’! Nay, according to Dr. Lankester, neither of them are poisons, though spirits are very bad. “ Intoxicating liquors ought not to be denominated poisons.” Well, gentlemen, if our learned critic will be nice, we can have no objection. We only wish to be accurate, and, therefore, I do not say that alcoholic wine, including the good water, is a ‘poison,’ but that it is intoxicating (from the Greek toxikos), that is, poison¬ ous. If you wish for further explanation, then I say, poison is a thing of quality—the physiological power of disturbing normal action or structure,—and is therefore applied to a class of effects varying widely in degree, tho not in kind, from the sting of a bee to the bite of a rattlesnake _ If spirits are not food, nor indifferent like sawdust, then they are poisonous, or, in ot her words, poison diluted. And the same must be asserted of fer¬ mented drinks, just so far as they disturb, or tend to intoxicate, the system of man. But Dr. Lankester “disagrees with his friend Dr. Carpenter, when lie argues from the fatal effects of a large dose of an alcoholic stimulant, against the use of a moderate15 [mean ing a lesser] quantity. For instance, one pound of salt would kill any one, but it did not follow that ten or twelve grains would injure or poison.” This argument is borrowed from the Lancet, and other medical journals, where some writers thought themselves very clever in employing it to evade the conclusions drawn hy the teetotaler from the fact that pure alcohol is essentially an acrid and corrosive poison in its topical action. It is indeed an attempt, gentlemen, in imitatiom of the juvenile method of catching birds. Dr. Lankester, relying on a popular fallacy regarding salt, would catch the Teetotaler by putting a little upon him—but I suspect he will find the difficulty is in the preliminary process. I, for one, shall certainly not suffer him to put the salt upon my theory, under the idea that it is a good thing—nor to draw his conclu¬ sion on the principle that ‘two blacks make one white—that the assumed virtue of salt disproves the asserted evil of alcohol. The fact is, I do not believe in salt; nor shall I do so until I have better proof of its dietetic utility than the traditional and worthless story of its absence breeding worms in Dutch criminals a long while ago. Since autumn last I have enjoyed better health than for many years past, and have nevertheless abstained from salt; while I knowr many persons enjoying excellent health who have not used it for years as diet^-tho once or twice as medicine. The experiment of the homceopathists to ascer¬ tain its real effects in small doses, show' that it is a very injurious article w:hen frequently introduced into the system. c The illustration selected by Dr. Lankester, therefore, is by no means so happy as he imagined it to be. If a person take any article, he may be killed either by its quantity or its quality. Two pounds of beef might kill by its quantity—i.e. by its bulk and pressure arresting the vital functions—but who could say that such w ould be a case of poisoning? Killing is not poisoning, tho poisoning may be killing. Llaviug made this distinction, I now proceed to put Dr. Lankester’s proposition anew: but with a different conclusion:—“If one pound of salt kills a person by virtue of its acrid proper¬ ties, then it does follow' that every ten grains of salt contained in the pound, did some the injury which, on the whole, proved fatal.” Nor can Dr. Lankester escape this infer¬ ence save by affirming that one part of the salt had no effect at all, or a very different b The words ‘ temperate5 and ‘ moderate/ are equally incorrect, when applied to a practice which is unreasonable or bad. It is time teetotalers ceased to concede their use to the opponent. c I know of several cases where its free use seems to have been concerned in producing spinal complaints and epileptic fits. Taylor, in his chapter on Poisons, classes salt under that head.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b30478534_0007.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)