Teetotalism in relation to chemistry and physiology : the substance of a lecture delivered in the Music Hall, Leeds, April 9th, 1851, under the auspices of the Temperance Society / by Dr. Frederick R. Lees.

- Frederic Richard Lees

- Date:

- [between 1800 and 1899?]

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Teetotalism in relation to chemistry and physiology : the substance of a lecture delivered in the Music Hall, Leeds, April 9th, 1851, under the auspices of the Temperance Society / by Dr. Frederick R. Lees. Source: Wellcome Collection.

8/12 (page 8)

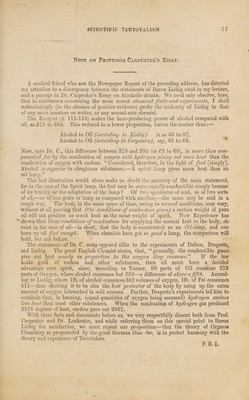

![effect from some other part. I affirm the same of alcohol as of salt. If a quart intoxi¬ cates or poisons a man, a glass does something of the same kind towards that end. In other words, there is no alteration of property or quality between the first and the last glass of wine or between the first and the last grain of salt. Lastly, Dr. Lankester announced to his audience that “alcohol had heat-producing properties.” If by that he meant that when burnt, in the body or out of it,—in other words, that alcohol gave forth heat like other decomposing things, as a sweating stack or a manure heap,—he was of course, if not monstrously wise, at least moderately accurate. Here, at last, we come to the theory of Liebig, and its relations to teetotalism. Before proceeding to consider this theory, however, I must briefly demonstrate the harmony of teetotalism with the natural laws, and explain the processes and structures of life. [Dr. Lees then proceeded with his exposition of the organic nature of man, the laws of life, and the adaptations of diet to the wants of the human economy. The body w‘as defined generally as an organ of action, and the various systems and functions were described as a living organism, that is, as characterized by warmth and movement. But heat radiates, and substance is worn down in acting. Thus the body in every part is perpetually subject to chainge, to wear and tear—hence the loss of head and of substance. Pood is the material adapted to restore this twofold loss, and is therefore of two kinds, viz .fuel-food to warm, nourishment to build up. The substances prepared by nature for fuel-food to the living house are oil, starch, gum, sugar, and cellulose, adapted to the various seasons and climates—those for nourishment are fibrine, albumen, and caseine, containing the various elements of the body and its tissues, in a solid form capable of assimilation. None of these substances have intoxicating or acrid properties; all are soothing or neutral in their physiological relations; and it must be confessed that all these 4 good creatures5 are accepted by the teetotalers, whose practice, thus far, is in clear harmony with natural arrangements. While food has two purposes to subserve, and is therefore of two sorts, drink has but one end to answer—that of a vehicle of move¬ ment or circulation; and hence in nature we have but one drink—literally 4 the water of life.5 Dr. Lees proceeded to consider the possible uses of alcohol as an element of diet. Alcohol could not be used as a fluid in the place of wrater, because it possessed diametrically opposite properties; it prevents digestion, it solidifies albumen, it stops the circulation. Alcohol was not nourishing food, since, in the first place, it was destitute of solidity, and could not, therefore, 4 stick to one’s ribs and, in the second, it wanted the greater num¬ ber of the essential elements of the tissues—as nitrogen, phosphorus, lime, sulphur, iron, etc., all of which must co-exist, and in a particular combination, to constitute nourishment.] Dr. Lankester, in advocating the 4 heat-producing properties ’ of alcohol, pretended that Liebig supported his views, “who ought to be regarded as an authority as great as Dr. Carpenterand contended, further, that “ persons recovering from indisposition, who could not take [digest ?] starch and sugar, would find alcohol [which only needs to be absorbed] to serve the same purpose.” Now, gentlemen, I dont think that you will be disposed to have a matter of this kind settled by the 4 authority5 of any man, but will unite with me in demanding the reasons for the opinions of either Professor Liebig or Professor Carpenter, I am thankful to both those gentlemen for many important facts which they have stated, but I also know that they are no better logicians than their neighbors; and, indeed, Liebig, with a noble frank¬ ness, has confessed to several erroneous inferences from-the facts stated in his earlier works. But I think, on this special point, that Dr. Carpenter has read the facts of Liebig better than Dr. Lankester, and I will attempt to show you why and wherefore I think so. Let me, however, here again protest against confounding together cases so distinct as those of health and disease. Of course, if a person be placed in such circumstances that he cannot be supplied with ordinary and proper fuel for vital heat, in a proper way, rather than permit him to die, it will be justifiable to give him extraordinary fuel that serves the needful end, even tho it does so badly, and in an unnatural manner. Amputation is good when an injured limb is mortifying; but is it, therefore, good to lose a sound limb? We must, then, fallback upon the old question, 44 Can the use of alcoholic drinks be justified as an article of ordinary diet?” I deny that Dr, Lankester is in possession of a](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b30478534_0008.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)