The experimental production of deafness in young animals by diet / by Edward Mellanby.

- Edward Mellanby

- Date:

- [1938?]

Licence: In copyright

Credit: The experimental production of deafness in young animals by diet / by Edward Mellanby. Source: Wellcome Collection.

14/32 (page 386)

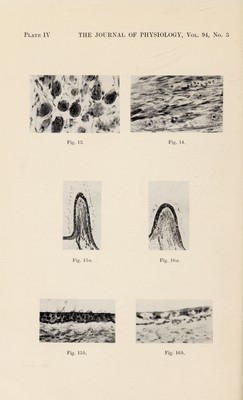

![are in keeping with those previously described [Mellanbv, 1935], where it was shown that, comparing the number of degenerating fibres in the cochlear and vestibular divisions of the 8th nerve in A-deficient animals, it was always found that the cochlear division suffered more severely than the vestibular division. Overgrowth of bone of the labyrinthine capsule. A glance at Figs. 1 and 2 shows another striking development in the internal auditory meatus of the vitamin A-deficient dog (Fig. 2). It will be seen that two massive pieces of bone fill up the meatus and leave little or no space for the branch of the 8th nerve. The bone appears on the whole to be of normal structure but the lower piece has a large cavity full of fatty tissue. The corresponding meatus of Fig. 1 (vitamin A-rich diet) is patent and the 8th nerve here has an uninterrupted passage to the brain. The filling of the internal auditory meatus at the modiolus end seen in Fig. 2 is only found in advanced cases of degeneration produced by the prolonged dietetic deficiency described, but all experimental animals, so far examined, brought up for a few months on similar diets show some such bony change. Another position where bony overgrowth is found is in the periosteal bone adjacent to the brain and to the internal auditory meatus. This new bone can be seen by comparing Figs. 8, 9 a and 9 b, which are low power photographs of the labyrinthine capsule of dog I (Fig. 8) and dog II (Figs. 9a and 96). In Fig. 8 (diet rich in vitamin A) the meatus and the cochlear division of the 8th nerve can be traced from the helix of the cochlea to the edge of the capsule. In Fig. 9 a the meatus is tortuous and the exit of the nerve from the brain cannot be seen, so that several sections are needed to trace its full course. This displacement is illustrated in Figs. 9a and 96; Fig. 96, where the exit of the 8th nerve or its remains is clearly seen, represents a section about 2-5 mm. from that shown in Fig. 9 a. The depth of bone between the basal whorl of the cochlear helix and the brain is much greater in Fig. 9 a (from A-deficient animal) than in the control (Fig. 8). The cancellous nature of the new bone is also clearly seen in Figs. 9 a and 96. This increase in periosteal bone is more clearly demon¬ strated in Figs. 10 and 11 representing sections cut in a plane at right angles to those of Figs. 8 and 9 a and 96. It will be seen that whereas in the normal dog (Fig. 10) the bone on each side of the internal auditory meatus is thin, in Fig. 11 it is greatly thickened, due to the laying down of new periosteal bone, which appears to be of the ordinary cancellous type. There is no excess of osteoid tissue, nor is there any evidence of the](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b30631087_0014.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)