The influence of heredity on disease : with special reference to tuberculosis, cancer and diseases of the nervous system a discussion / opened by Sir William S. Church, Sir William R. Gowers, Arthur Latham and E.F. Bashford.

- Date:

- 1909

Licence: In copyright

Credit: The influence of heredity on disease : with special reference to tuberculosis, cancer and diseases of the nervous system a discussion / opened by Sir William S. Church, Sir William R. Gowers, Arthur Latham and E.F. Bashford. Source: Wellcome Collection.

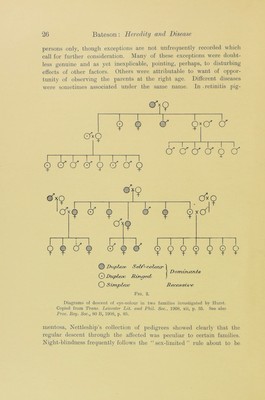

29/162 (page 25)

![the critical distinction between the dark and the light eye, as Hurst found, turns on whether there is pigment or not on the front of the iris. It is not always easy to see whether the pigment is present or not, but with some trouble it can be made out. The ordinary blue eye is one in which there is no pigment on the front of the iris, while in the brown eye there is pigment on the front. When there is pigment there, it may be transmitted, but when there is none in the parents, the children have none of it. The pigment may be spread over the whole iris, or restricted to some extent, after forming a ring round the pupil. Either type may be pure or impure in respect of eye-colour. The presence of the pigment is a dominant. If a parent is pure dominant, all the children will have colour in the iris ; if one parent is impure in the character and the other parent devoid of pigment in the iris, then on an average half the children will have eyes thus pigmented and half have “ blue ” eyes. Examples of some of these possible matings are shown in the diagrams copied from Hurst (fig. 2, see p. 26). One of these shows that a woman who has no colour in her iris, married to a man also without colour, was unable to transmit the colour to children, though her father had colour in his iris. Hurst examined 101 children of such parents, and all were without the pigment. These simple rules so far have been studied only on a small scale. Hurst traced them amongst the people in his own village in Leicestershire, and not until they have been followed out on a larger scale can it be stated with confidence that no exception can be found to them. Professor Bateson proceeded to show that similar rules can frequently be traced in the descent of certain human diseases and defects. In illustration he exhibited pedigrees of brachydactyly (after Farabee and Drinkwater), remarking that in the three instances in which the descent of a variation apparently meristic had been followed out the less divided condition was found to be a dominant. The other two examples were the abbreviated tail of the Manx cat and the aborted coccyx of the “ rumpless ” fowl (Davenport). Other similar pedigrees were shown relating to keratosis or tylosis palmarum, epidermolysis bullosa, diabetes insipidus, retinitis pigmentosa, irideremia or coloboma, ectopia lentis, and night-blindness. Several of these were taken from the work of Nettleship and from the collections of Gossage. [Other such pedigrees exist for complete abortion of the fingers, split hand and foot, distichiasis, ptosis, certain oedematous conditions of nervous origin, &c.] For most of the diseases named the rule commonly holds that transmission is through the affected 9,](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b28135726_0029.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)