Thirty-sixth annual report of the directors of James Murray's Royal Asylum for Lunatics, near Perth. June, 1863.

- James Murray's Royal Asylum for Lunatics

- Date:

- 1863

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Thirty-sixth annual report of the directors of James Murray's Royal Asylum for Lunatics, near Perth. June, 1863. Source: Wellcome Collection.

47/112 (page 41)

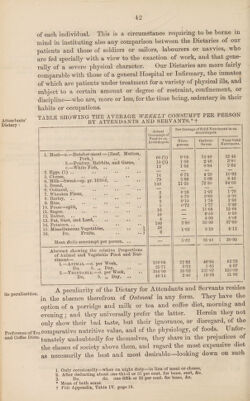

![physical exhaustion and of tissue-waste. The physiological require¬ ments of the system are, therefore, much greater than in the case of pauper patients—even the out-door working classes thereof; the tissue-waste is greater, and its due repair or replacement is demanded at the expense of a correspondingly larger amount of substantial nutri-Food in re]atio . ment. Moreover, in the case of our attendants and servants, a certaint0 work- amount of work is exacted and obtained; the food is supplied specially with a view to this end, and must be correspondingly liberal and nutritious, else we fail in our object. Dr Letheby* shows that the same man, who, while leading simply a vegetative life, requires for the performance of the vital operations a daily average of 16 oz. of solid nutriment, must have, when he becomes a soldier, 24 oz., and when he becomes a Yorkshire labourer or railway navvy, 51 oz. All statistics go to prove that work and food stand in an intimate or in¬ separable relation to each other; and that, where a high quality, or large amount of work, whether bodily or mental, is required, the food- Economy and supply must be correspondingly liberal. Such a procedure is the most Dieting. j economic as well as the most scientific. Whatever improves physical health or maintains it at its highest degree or point of usefulness is economical, inasmuch as it secures the largest possible return in work in proportion to the expenditure in food; inasmuch as disease and ill health are always expensive, always attended with, or lead to, loss in a great variety of ways. Even in a financial or pecuniary point of view—in the merely mercantile or profit-and-loss aspect of the ques¬ tion—it is clearly our best policy or interest to supply a class of officers, on whose vigour of body and mind so much of the prosperity or usefulness of an Asylum depends, with an abundant and adequate supply of the most suitable nutriment. On the other hand, we do not supply food to our Patients in order that they may work; but they work in order that they may properly digest their food, and generally improve their physical and mental health. The 2 classes of persons we have been contrasting—Attendants and servants of the Institution on the one hand, and Pauper patients on the other—are, in this respect, quite differently circumstanced. The one class is here as workers—paid and fed as such ; the more work they contribute, the more useful they are,—the more profitable and satisfactory our invest¬ ment in their services. The other class comes here as patients to be treated for mental, and generally also for associated physical, disease; in invalids a large proportion of cases work is impossible or inexpedient; and wherein. relation to l-l 11) 0 * it is both possible and expedient, it is prescribed just as regimen, medicine or moral treatment is prescribed,—as a remedial measure, its nature and amount being suited carefully to the capabilities or requirements * Vide Table IX. Appendix, page 24. .](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b30302316_0047.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)