The vocabulary of philosophy, mental, moral, and metaphysical : with quotations and references for the use of students / by William Fleming ; edited by Henry Calderwood.

- Date:

- 1876

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The vocabulary of philosophy, mental, moral, and metaphysical : with quotations and references for the use of students / by William Fleming ; edited by Henry Calderwood. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

514/590

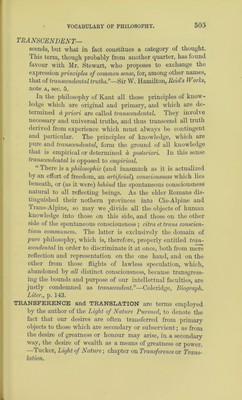

![50 i TRAIN OF THOUGHT— “ The parts of any total thought, when subsequently called into consciousness, are apt to suggest, immediately, the parts to which they were proximately related, and mediately, the whole of which they were constituent.” Hobbes, Leviathan, part i. ch. 3 ; Human Nat., p. 17 ; Reid, Intell. Pow., essay iv. TRANSCENDENT, TRANSCENDENTAL (transcendo, to go beyond,'to surpass, to be supreme).—[(1.) In Kant’s sense, tran- scendental applies to the conditions of our knowledge which transoend experience, which are a priori, and not derived from sensative reflection. (2.) The speculative problems which concern supersensible or supernatural being, tran- scending the range of sense and consciousness.—Ed.] Transcendental is that which is above the praedicamental. Being is transcendental. The prcedicamental is what belongs to a certain category of being; as the ten sumrna genera. As being cannot be included under any genus, but transcends them all, so the properties or affections of being have also been called transcendental. The three properties of being commonly enumerated are unum, verum, and bonum. To these some add aliquid and res: and these, with ens, make the six transcendentals. But res and aliquid mean only the same as ens. The first three are properly called transcenden- tals, as these only are passions or affections of being, as being. “ In the schools, transcendentalis and transcendens were convertible expressions employed to mark a term or notion which transcended, that is, which rose above, and thus con- tained under it, the categories or summa genera of Aristotle. Such, for example, is being, of which the ten categories are only subdivisions. Kant, according to his wont, twisted these old terms into a new signification. First of all he distinguished them from each other. Transcendent (transcendens) he em- ployed to denote what is wholly beyond experience, being neither given as an a posteriori nor a prion element of cog- nition—what therefore transcends every category of thought. Transcendental (transcendentalis) he applied to signify the a priori or necessary cognitions which, though manifested in, as affording the conditions of, experience, transcend the sphere of that contingent or adventitious knowledge which we acquire by experience. Transcendental is not therefore what tran-](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b2199531x_0514.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)