The skeleton in the flying lemurs, Galeopteridae / by R.W. Shufeldt.

- Robert Wilson Shufeldt

- Date:

- 1911

Licence: In copyright

Credit: The skeleton in the flying lemurs, Galeopteridae / by R.W. Shufeldt. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The Royal College of Surgeons of England. The original may be consulted at The Royal College of Surgeons of England.

42/72 (page 190)

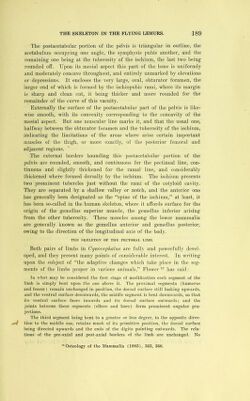

![inaniiiuil liabitually carries its limbs in tliis position, although the climbing Guleopithecus and the Sloths are not far from it. It is, however, very nearly the normal position of some Reptiles, especially the Tortoises, although it is ill adapted for anj’thing but a very slow and clumsy mode of progression. In Cj/naccphalus the limuerus makes the usiial articulations w'itli the scapula proximally, and the radius and ulna distally, that are seen among mammals generally. These articulations are in all cases extensive and the joints very perfect anatomically. The left humerus of the colugo (tigure 15) offers the following points for examination, some of which are better seen in the right humerus (figure 16) from the same skeleton, this being due to the different posi- tions in which the bones w'ere photographed. Its characters, including its length ami to some extent its size, vary somewhat in various in- dividuals. it is considerably shorter than the ulna or the radius; in man it is the longest bone of the arm. N'iewed in its entirety, upon either its direct inner or outer aspect, the humerus is seen to possess for its continuity the true “sigmoid curve.” This curve starts at the head and terminates with the trochlear extremity. Ignoring the prominent ridges its shaft is for the most part subcylindrical in form, the principal departure being at the distal end which is ex- panded to support the trochlejB for the bones of the antilji'achium. It is uniformly smooth, and pierced by an oblicpie, nutrient foramen situated about 2 centimeters distad of the articular part of the head, on the posterior aspect. 'riie very conspicuously elevated deltoid ridge with its thickened edge extends down the shaft, on its anterioi’ aspect, for about one-third of its length. It commences at the head and slopes away rather abruptly distally. Its nearly straight free margin is almost parallel to the shaft’s long axis, its sides being sjiiooth. On the other hand the supinator ridge is low, sharp, and thin, extending from the extej'iial condyle almost to a middle point of the shaft, following accurately the lower sigmoidal curvatui-e of the latter, where it is gi’adually lost. Among mammals we rarely meet with the humerus possessing a more perfect head than it does in CynocephuUis, in which genus it is almo.st a complete and entirely smooth hemisphere. For the most part its articular surface is distinctly differentiated by its circular limiting line and surrounding shallow groove or neck, the major part of which is seen on ])Osterior view. It I'eminds one of the humeral head of anthropotomy and surmounts the shaft in a very similar manner (figure 15). Upon either side of it the greater and lesser tuberosities are well developed, the comparatively deep bicipital groove passing the latter down the shaft and the side of the deltoid ridge. At the distal extremity of the bone, posteriorly, the olecranon fossa is very deep and markedly defined. Its osseous base is thin, and may](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b22419020_0044.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)