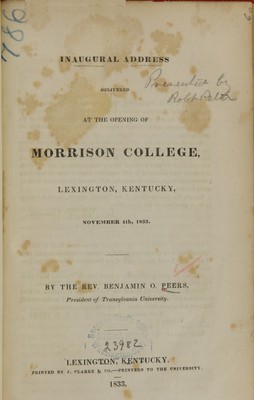

Inaugural address delivered at the opening of Morrison College, Lexington, Kentucky : November 4th, 1833 / by the Rev. Benjamin O. Peers.

- Peers, Benjamin O. (Benjamin Orrs), 1800-1842

- Date:

- 1833

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Inaugural address delivered at the opening of Morrison College, Lexington, Kentucky : November 4th, 1833 / by the Rev. Benjamin O. Peers. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the National Library of Medicine (U.S.), through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the National Library of Medicine (U.S.)

5/32

![[5] norantthan the horse he rides, was, at the corresponding pe- riod of life. His present superiority though ascribable in part to native advantages, is owing in a good degree to education; for grown men have been found wild in the woods but slightly elevated above the beasts around them. As great a contrast is presented us, if we compare the in- dividual himself in manhood, with what he was in infan- cy. Napoleon, who wielded the sword for the conquest of nations, was once unable promptly to carry his hand to his mouth. Sir Isaac Newton, whose vast mind seemed to as- pire (and with much success too,) to comprehend every thing in the heavens and on the earth, was at one time so igno- rant as to have to learn the simple fact that fire would burn him. This amazing transition from helplessness to power, from ignorance to knowledge, is entirely the product of educa- tion. Not that I ascribe creative power to education. This it does not possess. It exerts only a modifying influence. For the existence of our faculties we are indebted to the Creator, but their first manifestations and subsequent devel- opement we owe altogether to education. Nature imparts to us susceptibilities, but these susceptibilities, unawak- ened by external objects must lie forever dormant. Suppose the case of a mind equal to that of Newton, encased in a body destitute of senses; no eye, no ear, no taste, no smell nor feeling; whatever might be its native superiority, (if we can affirm inequality of minds) it must of necessity remain un- known to others, and, so far as we have means of judging, unknown even to itself. Mind like the electric fluid, lies dormant and unperceived till it is excited into action and no- tice as it were by the attrition of external objects. Hence we may learn the nature and objects of education. Did man enter the world in a stale of full maturity both of body and mind, as was probably the case with our first parents, there would be no occasion for education; that being accom- plished by nature, which now devolves on circumstances and art. But he is ushered into being, in a condition the farthest possible removed from maturity. Without an idea.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b2114655x_0005.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)