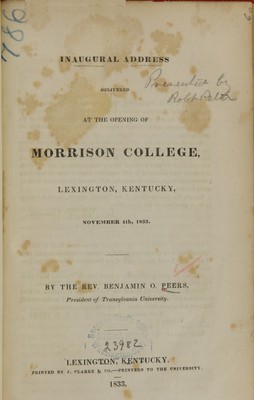

Inaugural address delivered at the opening of Morrison College, Lexington, Kentucky : November 4th, 1833 / by the Rev. Benjamin O. Peers.

- Peers, Benjamin O. (Benjamin Orrs), 1800-1842

- Date:

- 1833

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Inaugural address delivered at the opening of Morrison College, Lexington, Kentucky : November 4th, 1833 / by the Rev. Benjamin O. Peers. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the National Library of Medicine (U.S.), through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the National Library of Medicine (U.S.)

6/32

![[ 6] without a sensation on which to hase an idea, he commences his career in a world filled with innumerable objects inviting his acqaintance, and a knowledge of whose properties is es- sential not only to his well-being but even to the preserva- tion of his existence. To give him this knowledge, to di- rect him in the formation of this acquaintance, and to qualify him by a course of superintended practice, for the inde- pendent use of his various faculties; in short to convert the infant into the man, is the important business of education. From this view of the subject, it is evident, that, although the process of education begins with the very first sensation,, and continues until death; (the entire course of life being nothing more than a protracted course of education;) it is only with reference to that period which intervenes between birth and manhood, that I propose at present to consider it. This may be denominated the period of education. It is the probationary stage of life; the time allotted by nature for preparing to participate in its busy scenes. How preposter- ous then, to attempt to accomplish in two or three years, that for which God has assigned a period of twenty. How ab- surd the pretensions of all those who presume to dispense with time and labor in the tardy process of education. Uni- versal analogy testifies that every thing of importance is of deliberate growth. Nothing is so pernicious in intellectual culture as too great haste, and yet nothing is more common. Were the growth of mind like that of a mineral, by external accessions piled on by foreign causes, the case might be dif- ferent. But it resembles rather that of an animal, whose increase is the result of the assimilating action of its own powers; and the animal constitution forced either by dis- ease or art into premature magnitude, is never healthy. Our inquiries are to be subjected to still another limita- tion. The progress of education during the period specified, is in a great degree spontaneous. The mind possesses na- turally a self-educating tendency, from which it results that its development is commenced and carried on in some form or other, without the aid and direction of art. Within a](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b2114655x_0006.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)