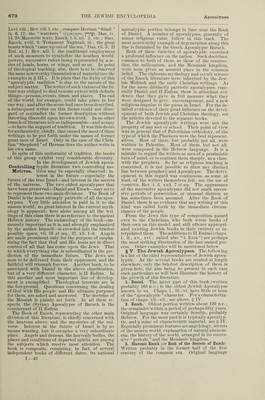

Volume 1

The Jewish encyclopedia : a descriptive record of the history, religion, literature, and customs of the Jewish people from the earliest times to the present day / prepared ... under the direction of ... Cyrus Adler [and others] Isidore Singer ... managing editor.

- Date:

- 1901-1906

Licence: In copyright

Credit: The Jewish encyclopedia : a descriptive record of the history, religion, literature, and customs of the Jewish people from the earliest times to the present day / prepared ... under the direction of ... Cyrus Adler [and others] Isidore Singer ... managing editor. Source: Wellcome Collection.

729/752 (page 671)

![Apocalypse To tliis description of the literary peculiarities of the Jewish Apocalypse might be added that in its distinctly eschatological portions it exhibits with considerable uniformity the diction and symbolism of the classical Old Testament passages (see below). As this is true, however, in like degree of the bulk of late Jewish and early Christian eschatological literature, most of which is not apocalyptic in the proper sense of the word, it can hardly be treated as a characteristic on a par with those described above. § III. Origin and Materials. The origin of the .lewisli Apocalypse is to be sought chiefly in the natural development of certain well-defined tenden- cies in the national literature; possibly also in part, as some have thought, in the intlueuce of foreign religious ideas and literary models. The earliest known example of a Jewish Apocalypse is the Book of Daniel (middle of the second century is.c.), with which book the distinct beginning of a new branch of literature is made (though some hold that a part of the Book of Enoch is anterior to Daniel). But the author of Dan. vii.-xii., though a pioneer and an originator in this department, could hardly be called the creator of the Jewish Apocalypse. Nearly every one of the characteristic features of his work is to be found well established in the earlier literature of his people. Furthermore, the subse(iuent comiiosi- tions of this class were not wholly or even largely developed from the materials provided in this book. Like Daniel, and together witli it, they were a char- acteristic product of the times (see below). The ex- tensive Enoch literature, which begins to make its appearance soon after this, is in itself a siilbcient demonstration of the fact. It is evident Uiat the materials for this sort of composition were at that time ready to hand. On the other side, the Book of Daniel certainly did determine, to a considerable ex- tent, how the existing materials should be used in the apocal3ptic tradition and in the popular escha- tology. Its influence on both the religious and the literary side was veiy great. The most nearly related precursor of the Jewish Apocal^’pse was the chai’acteristically developed eschatological element in the later Hebrew proph- ecy. The Hebrew ideas concerning the last things were in many respects very similar to Late those which were held by the surround- Hebrew ing peoples; but the same fundamen- Prophets. tal beliefs which shaped the religious life of the nation, and determined the development of every other department of its re- ligious literature, showed themselves to be fully op- erative here also. It was the doctrine of the chosen people, especially, which was the controlling influ- ence in the growth of Hebrew and Jewish eschatol- og}'; and this is easily recognized also as the domi- nant idea in the Jewi.sh Apocalypse. The hope for Israel cherished by the later proph- ets finds its completest and most exalted expression in Isa. xl.-lxvi., where the future of the nation is painted in vivid colors and on a magnificent scale: “Israel is the chosen people of the one God, who has plainly declared His purpose ever since the be- ginning. Though it is now a despised race, trodden under foot, its glorious future is certain.” As the horizon of the Jews gradually widened, and the\' saw more plainly their relative position among the nations of the earth, and the impossibility of gain- ing any lasting political supremacy, the belief in an age to come, in which righteousness and the true religion should hold undisputed possession, came more and more prominently into the foreground. In the Maccabean age, especiall}% under the stress of severe persecution, this belief, and the various doctrines connect(‘d with it, received a mighty im- pulse, Thus out of the hope nourished by “ Deutero- Isaiah ” and his fellows (who are only less eloquent than he in giving voice to it) there grew of necessity the doctrine of “ the world to come ” {hn-'olam-ha-ba); the ever-present contrast between which and “ this world ” is one of the fundamentals of apocalyptic literature throughout its whole his- tory, though these particular forms of expression are late in appearing (see, however, Enoch, Ixxi. lo). Thus, the purpose of tlie whole elaborate sj'mbolism of Dan. vii. is to be foimd in the final antithesis be- tween the successive empires of this world and the “everlasting kingdom” of the saints of the Most High (verses 18, 27). Compare also especially H Esd. vii. 50, viii. 1. The more unlikely it seemed that Israel would ever be able to get the upper hand of the surround- ing nations, the stronger grew the feeling that the final triumph would be preceded by a complete overthrow of the existing order. The present age would come to a sudden end; and a new age, ushered in by the “day of the Lord,” would take its place. This “end” (D'D'H nnnX) would be “ Day of announced by great portents, and con- the Lord.” vulsions of nature, “signs” on the earth and in the heavens; and in speak- ing of the.se things, a phraseology highl}' figurative and mj’sterious became fixed in use. See, for example, Lsa. xxiv. eUeq., xxxiv. 4, Ixvi. 15; Zeph. i. 15; Zech. xiv.; .Joel, iii. 3 et xeq. [ii. 30 etkeq.^, etc.; and com- pare in the New Testament Matt. xxiv. 29, and the synoptic parallels. These ideas and images were a fruitful source of material for the apocalyptic wri- tings; compare, for example, Sibyl, iii. 796-807; II Esd. V. 1-12, vi. 20-28; Ajioc. Bar. xxvii., liii., lx.x.; Enoch, xci.-xciii., c.; H Esd. (“5 Ezra”] xv. 5, 20, 34-45; xvi. 18-39, IVIoreover, the day of Israel's triumph was to be a day of judgment on the Gentiles. The various pha.ses of this idea made so prominent by the later prophets—a series of final bloody wars, in which the oppres.sors of Israel shall fall: “Gog and Magog” (Ezek. xxxviii. et mq.), the judgment and punish- ment of the nations by Jehovah (Zeph. iii. 8; Joel, iv. [iii.] 2, 9 et seq.)—are elaborated in characteristic manner by the apocalyptic writers. The most stri- king example is the prediction in Dan. xi. 40-45 (see above, g H. 4). The idea of a final triumph of God and His heavenlj' hosts over evil spirits also followed natu- rally, and kejit pace with the development of the Jewish angelology. The “ guardian angels ” of Dan. ix.-xii., and the punishment of the “fallen stars,” which occupies so much space in the Enoch litera- ture, are only elaborations of beliefs which had already received distinct expression; compare Isa. xxiv. 21 et seq. (a most important pas.sage), xxvii. 1; Ps. Ixxxii.; Dent, xxxii. 8 (Greek); Job, xxxviii. 7, etc. The appearance of the evil spirit “ Azazel ” in Lev. xvi. 8 et seq. is proof that the names of angels and demons were in common use before the days of Daniel and Enoch. But the eschatological teachings current among the Jews at the beginning of the second century B.c. were not concerned merely with the fate of the nations, and of the people Israel in particular. As the coming “ day of the Lord ” was looked upon as a time when wrongs were to be set right, it was natural—indeed necessary—that the expected judg- ment should also appear as the final triumph of the righteous over the wicked, even in Israel. Thus Mai. iii. 1-5, 13-18, 19-21 [iv. 1-3]; Zeph. i. 12; Zech. xiii. 8 et .seq. Hence the doctrine of the resurrection of the](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b29000488_0001_0735.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)