The treasury of natural history, or, A popular dictionary of zoology / by Samuel Maunder.

- Maunder, Samuel, 1785-1849.

- Date:

- 1870

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The treasury of natural history, or, A popular dictionary of zoology / by Samuel Maunder. Source: Wellcome Collection.

780/856 (page 758)

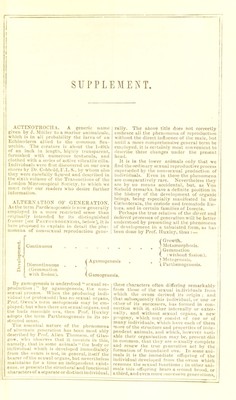

![T)8 ^mpplrmeut- before the return is made to sexual repro 1 duction.” Such being a general statement of the fucts representing so many links, as it were, in the complicated chain of phenomena of i non-sexual reproduction, we now proceed to adduce a selection of illustrations by which this interesting law of alternate generation may he clearly understood. ; Probably the most instructive and at the | same time the most practically useful ex- I emplification which can be brought forward. ia that which we derive from a consideration | of the development of a cestode parasite or : Entozoon which, unfortunately, infests the 1 human body. In this view, therefore, we 1 particularly invite attention to the natural I history of the common Tapeworm, or Tieuia solium. I The Solitary Tapeworm (so misnamed from the false notion that only one lives in II tapeworm; a. single joint or proqlot TI3 : B, HEAD OF THE OOLONT. OK STROBIL* I the same person at once), in the full-grown 1 condition,is not, strictly speaking,ucreature I j or animal, but rather a great many creatures i' attached to one another, so as to form a 1 colony, or, more scientifteallv. the Strobila. i [See Stkobila, below.] This colony is 1 usually composed of several hundred joints. and each of these joints represents un intii- 1 vidual worm (proploUu'i; those which are i nearest to the lower end for so-called tail of i the Tapeworm) being sexually mature. | They are indeed hermaphroditic,/, e. having both male and female reproductive organs. 1 Those feebiy developed joints which form ! the so-called neck of the worm are imperfect I or immature individuals ; whilst the little i head is neither more nor less than a single Individual (equivalent to a joint or pro- glottis) singularly modified, and furnittied j with an apparatus by which the Krobili or ■ colony is, as it were, securely anchored to the walls of the bowel of (lie unhappy person which the Tupeworin infests. The rnan, woman, or child, thus infested, or harbour- ing the parasite, is technically said to be the /tost, because he or she entertains its presence Looking, therefore.at tlie mature proglottis as the adult individual worm, we hare now to consider the manner in which it repro- duces itself. After the proglottis (which is furnished with male and female reproductive organs) i has undergone impregnation by contact with another proglottis, there results from this the formation of eggs within it, which eggs, whilst 6till within the body of the parent, develope into embryos, the latter still retaining the egg coverings. At this time the proglottis is about to undergo a passive migration, for having detached itself from the strobila, it is si-on expelled from the bowel of the host, and therefore finds its way into some cesspool, or it mav be into the open fields. The proglottides move about for a time, but the growth of the multitudes of embryos within causes the , proglottis sooner or later to burst, and the embryos thus become dispersed : some are thus conveyed down drains and sewers, others are lodged bj the roadsides in ditches and waste places, whilst multitudes are scattered far and near by winds or insects in every conceivable direction. Each em- bryo is furnished with a special tHiring ap- paratus, having at its anterior end three pairs of hooks ; the entire eroup or family, therefore, of any single proglottis is called the “six-hooked brood.” After a while, by accident, as it were, a pig coming in the way, either of these embry os or of the proglottides, swallows them alone with other matters taken in as food. The em- bryos, immediately being transferred to tl»e digestive canal, escape fiom the. eggshells and bore their way through the living tissues of the animal, and having lodged themseives in the fatty parts of the flesh, they there rest to await their further transformations or destiny. The animal thus infested becomes measled.and thus it is that we are acquaint- ed with measly pork. In this situation the embryos drop’their hooks or boring appa- ratus. and become transformed into the Ci/sticercus crlluhwcE. A portion of this mensled meat being eaten by ourselves, either in a raw or imperfectly cooked con- dition, transfers the Cvsticercus to our own alimentary canal, in which situation the Cysticereus attaches itself to the wail of the human intestine, and, having secured a good anchorage, begins to grow ut the lower or caudal extremity, producing numerous joints or buds to form the strobila or Tapeworm colony. Thus the cycle of life-development is com- pleted, and we have a simple alternation of generation in which the immediate pn>- duct of the proglottis lor sexually mature individual) is a six-lu*okcd brood : by meta- morphosis ti>e latter becomes transformed into the Cvsticercus, having a head with four](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b24864201_0780.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)