Copy 1, Volume 1

Hand-book of chemistry / Translated by Henry Watts.

- Gmelin, Leopold, 1788-1853

- Date:

- 1848-1872

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Hand-book of chemistry / Translated by Henry Watts. Source: Wellcome Collection.

44/562 (page 20)

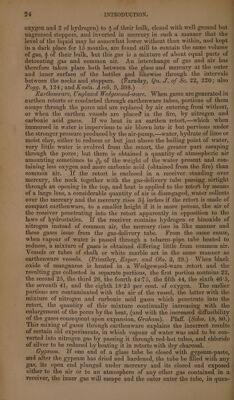

![linear dimensions, The atomic theory seeks to explain the structure of crystals by attributing a distinct form either to the atoms themselves, or if these be regarded as spheres, to aggregations of several of them. (Ved. Affinity.) The advocates of the dynamic theory proceed partly from the hypothesis that every solid body differs from a fluid in this respect, that the cohesion of its particles is of different amount in different directions, and further, that in a crystal these directions extend through the whole mass in straight polar lines. ADHESION. That kind of attraction which acts at infinitely small distances only between bodies of different natures, giving rise to the union of these bodies into a heterogeneous whole called a Aiature or Mechanical Com- bination, which may in most cases be overcome by mechanical force. It appears to be exerted between all kinds of matter, imponderable as well as ponderable, but in various degrees. [On the adhesion of im- ponderable bodies to ponderable bodies see the part of this work which treats of Imponderables.] Respecting the adhesion of ponderable bodies to one another the following cases must be distinguished :— 1. Adhesion between elastic flurds. Diffusion of Gases.—All gases, even when under existing circum- stances they do not enter into chemical combination, yet diffuse them- selyes through one another and form a uniform mixture, though their specific gravities may be very different and they may be kept externally at perfect rest. If, for example, two bottles be connected by an upright glass tube 10 inches long and 54, inch wide, the upper bottle being filled with hydrogen, nitrogen, binoxide of nitrogen, or common air, and the lower with the heavier gas carbonic acid, or the upper with hydrogen and the lower with common air, nitrogen, oxygen or binoxide of nitrogen, a portion of the heavier gas will after a few hours be found in the upper bottle, and after two or three days both bottles will contain the two gases in the same proportion (Dalton, Phil. Mag. 24, 8). The same result was obtained by Berthollet (Mém. d’Arcueil, 2, 463) with a tube 10 inches long and + of an inch wide placed in a cellar where no change of temperature could take place to set the gases in motion. When hydrogen was the gas contained in the upper vessel the two gases were found to be uniformly mixed in 1-2 days; but when air, oxygen, or nitrogen, was contained in the upper vessel and carbonic acid in the lower, several weeks elapsed before the mixture became perfectly uniform. If a cylinder filled with any gas and placed in a horizontal position be made to communicate with the external air by means of a knee-shaped tube in such a manner that the end of the tube is directed downwards when the gas is lighter and upwards when it is heavier than the air, the gas will gradually escape from the cylinder, its place being supplied by the air. According to Graham, . Of 100 volumes of gas there disappeared, Sp. gr. In 4 hours. In 10 hours. 1 Hydrogen - - - - - 81°6 - ~ 94°5 8 Light carburetted hydrogen - - 43°4 ~ - 62°7 8:5 Ammonia - - - - - 41°4 - - 59°6 14 Olefiant gas - - . - 34°9 - “ 48°3 22 Carbonic acid - - - - 31°6 - - 47:0 Be Sulphurous acid - - - - 27°6 - - 46:0 35'4 Chlorine .- - - - - 23:7 - - 39°5 a](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b33289190_0001_0044.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)