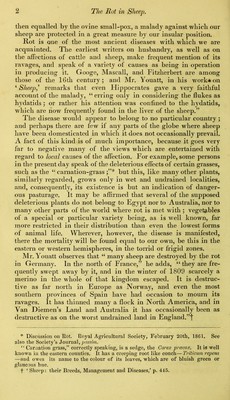

The rot in sheep : its nature, cause, treatment, and prevention : illustrated with engravings of the structure and development of the liver-fluke / by James Beart Simonds.

- Simonds, James B. (James Beart), 1810-1904.

- Date:

- 1862

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The rot in sheep : its nature, cause, treatment, and prevention : illustrated with engravings of the structure and development of the liver-fluke / by James Beart Simonds. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The University of Glasgow Library. The original may be consulted at The University of Glasgow Library.

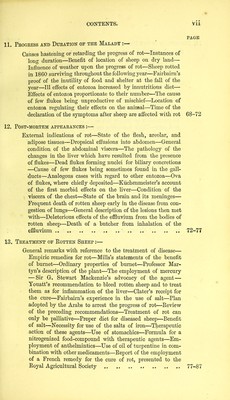

12/106 (page 4)

![dead bodies of rotten sheep were so numerous in roads, lanes, and fields, that their carrion stench and smell proved extremely offensive to the neighbouring parts and to passant travellers.” Ellis also describes another visitation in 1747, depending on a wet spring which succeeded a very mild winter. The rain, he says, began to fall at the beginning of May, and continued with but few intermissions throughout the month, as also that of June and part of July. 44 From all which,” he remarks, 461 would observe to my reader that a Midsummer rot ensued, and great numbers of vale-sheep became tainted by it, as did many also in the Middlesex grounds.” The year 1766 witnessed another and far more serious outbreak than that of ’47. It is thus spoken of by Mills in his Treatise on Cattle, 1776. 44 Too rainy a season is very prejudicial to sheep, as was remarkably experienced all over England in the summer of 1766, when whole flocks perished with the rot.” The next visitation in the order of time, of which we have been able to collect some particulars, is mentioned by Dr. E. Harrison in his Inquiry into the- Rot in Sheep and other Animals, 1804. He says that 44 in the year 1792 the country was uncommonly wet from the great quantities of rain which fell in the summer months, and this was a most destructive year to sheep and other animals. In the human subject, agues, remittants, and bilious autumnal fevers, were also prevalent in many places. Graziers soon took alarm and became very solicitous about their flocks. A breeder of rams informed me that to save his finest sheep he put them into closes which during an occupation of 40 years had never been known to rot, but he had the misfortune to lose them all. He was equally surprised to find that other pastures which had frequently produced the rot were this season free from it.” Harrison adds, that, 44 upon inquiry I found that the sus- pected land was so much under water this year that the sheep were obliged to wade for their food; and that pastures of a higher, and consequently of a dryer layer, were, from the deluge of rain, brought into a moist or rotting state.” We come next to 1809-10, which appears likewise to have been a period of great fatality in some localities. Fairbairn, who writes under the nom de plume of a Lammer- muir Farmer, states, in his Treatise on the Cheviot and Black- faced Sheep, that in 1810 his stock consisted of 2000 ewes, hogs, and dinmonts [shearling wethers], out of which he lost by rot during the winter and spring following above 800. He also says that in 1816 and ’17 the Lammermuir farmers suffered in many respects from the severity of the seasons. He describes 1816 as being very wet and cold, but comparatively free from rot in consequence of the low temperature which prevailed. He says,](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b2493088x_0014.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)