The Private Finance Initiative : sixth report, together with the proceedings of the Committee, minutes of evidence and appendices / Treasury Committee.

- Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons. Treasury Committee

- Date:

- 1996

Licence: Open Government Licence

Credit: The Private Finance Initiative : sixth report, together with the proceedings of the Committee, minutes of evidence and appendices / Treasury Committee. Source: Wellcome Collection.

201/228 (page 165)

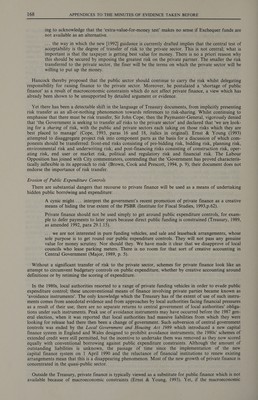

![The fourth issue concerns the distinction between free-standing facilities and those which constitute parts of larger integrated networks. When free-standing, the credibility of the bankruptcy threat is sub- stantially enhanced. However, private owners of such infrastructure assets may possess substantial monopoly power. The difficulties inherent in long-term forecasting of the usage of long-lived assets raises particular problems; the Government has emphasised that infrastructure contracts should be put out to tender, but has not yet clarified whether price regulation might be envisaged.* When part of a network, the privately financed link may be vital to network efficiency, thus weakening the credibility of the bankruptcy threat. When a tolled facility runs parallel to an inferior untolled facility, there is the ques- tion of whether assurances have been given to the private promoter that the untolled facility will neither be upgraded nor reprovided.° ADDITIONALITY Additionally is the term used in public expenditure contexts in order to pose the question whether a policy initiative leads to higher expenditure than would have occurred in its absence. Statements about ‘additionality’ are notoriously difficult to evaluate, because there is no counterfactual benchmark of what would otherwise have happened; this has been a fraught issue regarding European Union aid to projects and programmes in disadvantaged regions. Whether additionality is perceived to be desirable depends upon how the policy problem has been defined, and which constraints are perceived to be binding; for example, whether there is a ‘shortage’ of public finance for ‘worthwhile’ projects. Moreover, the Treasury has always explicitly linked the issue of additionality to the need to control the size of the public sector and to determine priorities rationally within pre-established totals. In the particular context of private finance for public projects, the key issue is whether recourse to private finance leads to higher spending in that ‘policy’ area, or is instead accompanied by offsetting reductions in public finance. An inhibition against the use of private finance has been the concern of government departments and public sector managers in general that recourse to private finance as a means of increasing capital expenditure would be frustrated by offsetting reductions by the Treasury to their public sector allocations. There are there- fore two aspects: the continuing desire of the Treasury to ensure that public finance is directed towards the areas which have the highest return, and the incentive effects of offsetting private finance against public expenditure allocations. There has been strong Treasury opposition to what might reasonably be characterised as non-policy driven additionality. In those areas of the public sector where there is a mixture of public and private provision, the investment expenditures of competitive private sector suppliers will shape the Government’s decisions ‘over a period of time, [about] how much the public sector needs to do in the same area’ (Treasury, 1988, para 15). Strengthening Treasury reassurances after 1989 that there would be (some) additionality (Treasury, 1993d) were clearly designed to counter the view that ‘ ... there is no point in promoting privately financed roads because the Treasury will simply claw it back by reducing public expenditure’ (Major, 1989, p.5). Nevertheless, the 1996-97 Red Book (Treasury, 1995b) demon- strates clearly that programmes deemed particularly suitable for the PFI are also those likely to suffer most from the cutbacks in public sector net capital spending. On transport, for example, the PFI has become substitutional rather than additional, with the public allocation cut in anticipation of growing PFI spend (p.121). Measurement of efficiency gains and additional financing costs The case for recourse to private finance hinges pivotally not only upon the existence of efficiency gains but also upon their magnitude being sufficient to offset the higher financing costs. The UK Government borrows more cheaply than private borrowers: while we cannot ignore the fact that the Government can raise money relatively cheaply because it is a large low-risk borrower, we must also take account of the benefits that tend to go with private finance, such as improved efficiency, low costs, and reduction in the risks falling on the taxpayer ... (Major, 1989, p. 4) The Treasury has not attempted to quantify the efficiency gains through better construction and oper- ation which are believed to be achievable through the use of private finance for infrastructure projects because: _.. the size of the efficiency gains would depend on the particular characteristics of individual projects. The use of private finance would sharpen incentives to control risk and achieve an adequate rate of return (Treasury, 1993a, p. 13). 4 ‘It may in some cases be appropriate to impose separate regulatory controls...’ (Treasury, 1992c, para 14). Policy is developing on a case-by-case basis. Whilst tolls on the BNRR are unregulated ‘since there are alternatives—the local toll-free roads and the government operated motorway network’ (Department of Transport, 1993, para 6), tolls on the Dartford crossings are linked to the RPI since the ‘undertaking ... represents a local monopoly’ (Department of Transport, 1994, para 4). 3 fie cae Office instructed the nationalised Caledonian McBrayne to withdraw its ferry service from the date of the opening of the Skye bridge.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b32218151_0201.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)