On an improved optometer for estimating the degree of abnormal regular astigmatism / by John Tweedy.

- John Tweedy

- Date:

- [1876]

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: On an improved optometer for estimating the degree of abnormal regular astigmatism / by John Tweedy. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by UCL Library Services. The original may be consulted at UCL (University College London)

1/6 (page 1)

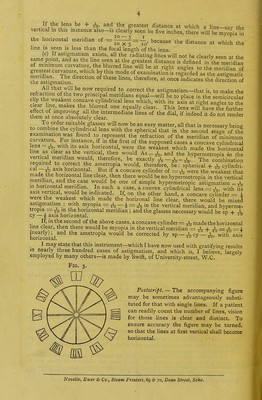

![[Reprinted, with additions and corrections, from the Lancet, Oct. 28, 1876.] ON AN IMPROVED OPTOMETER FOR ESTIMATING THE DEGREE OF ABNORMAL REGULAR AT the solicitation of a large number of ophthalmic surgeons, both in this country and abroad, I am induced to publish an account of an optometer that I have been in the habit of using both in hospital and private practice during the last four years, for the purposes of determining the existence of abnormal regular astigmatism, and of estimating its degree. Such being the primary object of this communication, I need not consider categorically the symptoms that attend this remarkable anomaly of refraction; but I shall explain, as briefly as possible, the optical conditions on which it depends, in order that the principles upon which the instrument is constructed may be better understood. What is called regular astigmatism, or simply astigmatism, exists when the refracting surface of the cornea, instead of being practically spherical, presents an appreciable difference of curvature in its two principal meridians. These principal meridians, which usually approach, but rarely exactly coincide with, the vertical and horizontal meridians of the eyeball, are always at right angles to one another, and are designated the meridians of minimum or maximum curvature, or of least or greatest refraction, according as they represent segments of a larger or smaller ellipse. But although there is a difference of curvature between the two principal meridians as compared with each other, the curvature throughout the whole extent of any given meridian remains constant and unbroken. In an eyeball so formed there are therefore two foci—an anterior one for rays contained in the plane of the meridian of maximum curvature, and a posterior one for rays contained in the plane of minimum curvature. For these reasons radiating lines described on a plane perpendicular to the visual axis cannot all be seen clearly and distinctly at the same distance, inasmuch as when the rays passing through the meridian of maximum curvature, or greatest refraction, are focussed on the retina, those passing through the meridian of minimum curvature towards the posterior focus are intercepted, and form a blurred diffusion-image. When, on the other hand, the rays contained in the meridian of minimum curvature, or of least refraction, have their focus on the retina, those passing through the meridian of maximum curvature will, after converging at the anterior focus, cross each other and form an inverted diffusion-image. So, also, a point of light can never be focussed on the retina as a point, but forms a diffusion-image, which varies in shape, direction, and extent, with the distance of the object, and the state of accommodation; being at one time linear, at another elliptical, and at another perhaps circular. It is, indeed, this very peculiarity which is expressed in the term astigmatism. In order to get rid of the inconveniences of these errors of refraction, it will be necessary to bring the two foci of the eye to the same plane, either by throwing the anterior one backwards by means of a diverging lens, or bringing the posterior one forward's by means of a converging lens. It is evident, however, that a spherical lens will not do this, because it refracts equally in all meridians ; but, happily, as Sir George Airy has pointed out, a cylindrical lens will (a lens being so named because it is a segment of a cylinder, and refracts only those rays that fall at right angles to its axis, which is itself plane). If, then, the anterior focus is at the retina, a convex cylindrical lens will be required to produce sufficient con- vergence of the rays contained in the plane of the meridian of minimum curvature to bring the posterior one forwards ; but if the posterior focus fall naturally on the retina, a concave cylindrical lens must be used to remove the point of convergence of the rays contained in the meridian of maximum curvature backwards to the retina. In the former instance there would be simple hypermetropic astigmatism, ASTIGMATISM. By JOHN TWEEDY, F.R.C.S. Eng., Clinical Assistant at the Royal London Ophthalmic Hospital, Moorfields.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21633666_0003.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)